The 35th Division was a Kansas and Missouri Division composed of the organized National Guard of both states. Ten thousand Kansas men and fourteen thousand Missouri men were mustered into the federal service on August 5, 1917, and received their training during seven long months at Camp Doniphan, adjoining Fort Sill, Oklahoma, near the town of Lawton. The Division consisted of the 69th and 70th Infantry Brigades, composed of the 137th, 138th Infantry, with the 129th Machine Gun Battalion; and the 139th and 140th Infantry, and the 130th Machine Gun Battalion; all of the 60th Field Artillery Brigade, which was composed of the 128th, 129th and 130th Field Artillery. The auxiliary troops included the 110th Engineers, 110th Trench Mortar Company; 110th Motor Supply Company; 110th Field Signal Battalion; 110th Train, consisting of a Sanitary Train, with four Ambulance Companies, and four Field Hospitals, and an Ammunition Train with four Motor Companies and four Horse Companies; and the Division Headquarters, with the Headquarters Troop M. P., the 128th Machine Gun Battalion, and the Division Quarter-Master Corps.

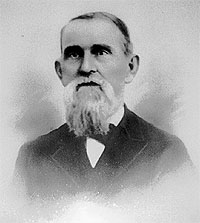

To bring the 8,500 Kansas men and the 14,765 Missouri men up to the divisional strength, then set at 27,000, draft men of Kansas and Missouri were added to the Division. A great deal of credit is due to Gen. Charles I. Martin, then Adjutant-General of Kansas, and Gen. Harvey C. Clark, then Adjutant-General of Missouri, who built up the skeleton frame, which existed at the time war was declared, into the splendid body of men which the Division afterwards became.

A list of the Kansas National Guard units together with their designations follows:

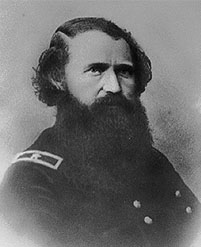

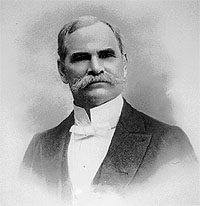

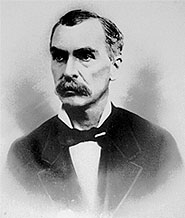

Maj.-Gen. Wm. M. Wright, a graduate of the Military Academy, in 1882, took command of the Division August 29th, 1917, and retained command of it until the Division’s arrival in France. He was, however, sent to France on a tour of the trenches, and Brig-Gen. Lucien G. Berry, who commanded the 60th Field Artillery Brigade, served as acting commander of the Division during most of his absence. General Berry was not a popular commander of the division, and during his command of it, some of the higher officers were weeded out including among others, Brig.-Gen. Harvey C. Clark, of Missouri; Col. Hugh Means of the 130th Field Artillery; Maj. Albert H. Krause, and Lieut. Col. Charles S. Flanders, who had been a Captain of the famous 20th Kansas in the Philippines. Many of the men who served in the division believe that these men should have been left in command, and that they were weeded out on account of either a real or a fancied prejudice against the National Guard. The probabilities are that some of the regular army officers with whom the division came in direct contact were not up to the usual standard of the regular army, and that the division was unfortunate in this respect. A historian of the 35th Division says that if General Wright could have remained with the division, it might have been a different story, and that he was an officer of wide experience who cared very much more for his men than for his personal reputation; that he was in every way fitted to lead the Division into battle, and commanded the confidence and loyalty of both officers and men.

When General Wright returned, on January 4, 1918, he inaugurated material changes in the training of his troops. General Berry had been acting division commander until January 2, 1918, and then Brig. Gen. Charles I. Martin, of Kansas had been the acting commander until General Wright returned.

British and French instructors taught the use of the bayonet, the hand grenade and the gas mask to the men at Camp Doniphan.

In April, after over seven months of hard drilling, the division began to move, and landed in England on May 7, 1918, and reached LeHavre on May 10th.

About June 6th, after training in the interval a few miles from the hard-pressed British line near Amiens, the division was sent to a quiet sector in the Vosges, by the far-famed “40 men, 8 horses,” box-car system, where they remained in the Arches area until June 30th, and on that morning they began the move toward the Wesserling sub-sector on the Vosges front. On June 15th General Wright was relieved of command and placed in temporary charge of the Third Army Corps. Brig. Gen. Nathaniel F. McClure assumed command.

Life was very quiet in the Vosges, although there was a German raid on the First Battalion, of the 140th Infantry, under Maj. Fred L. Lemmon, early in August, and three hundred Germans staged a raid on the 139th Infantry. These raids were probably in retaliation for raids put on in the latter end of July by Company C, 137th Infantry, which returned with five German prisoners, and by Company H, 138th Infantry, which returned with seven prisoners, leaving twenty German dead.

THE THIRTY-FIFTH DIVISION AT ST. MIHIEL

The first battle in which the Thirty-fifth Division took part was St. Mihiel. The Division was relieved from the Wesserling subsector and Gerardmer sector by September 1st, and was moved to concealed bivouac in the Foret de Haye, in the First Army Reserve, which was a dreary affair. That battle was so easy that the Reserve was never used, and the men lay in their pup tents in the soggy dripping woods, without even a chance to see the enemy, though under shellfire.

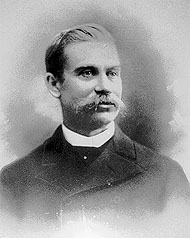

By this time, May, General Peter E. Traub had assumed command of the Division, and he led it into the Argonne.

THE THIRTY-FIFTH DIVISION IN THE ARGONNE

The Division was moved by some two hundred French trucks from their reserve at St. Mihiel to the neighborhood of Grange-le-Conte, in the woods east of Beauchamp, and remained there until the morning of September 26th, when the greatest battle in American military history, the Battle of the Argonne, commenced.

The Division formed the left flank of the First Army Corps, under Lieutenant General Hunter Liggett, with the 28th Division, under General Muir, a fine Pennsylvania National Guard outfit, and the 77th Division under General Alexander, a New York draft outfit as the other two divisions in the First Corps: on their right was the Fifth Corps under Cameron, and on Cameron’s right was the Third Corps under Lieutenant General Robert Lee Bullard.

It will be remembered that the battle was fought in a northerly direction between the Aisne River on the left and the Meuse River on the right; the extreme right of the Americans being to the north of Verdun, and the extreme left of the 35th Division was on the Aire River.

The First, Second, Third, Twenty-sixth, Thirty-second and Forty-second Divisions, perhaps the best troops of the A[merican] E[xpeditionary] F[orce], or rather the most experienced troops of the A. E. F., were held in reserve.

Five days before the battle started, General Traub relieved Brigadier General Martin of his command of the 70th Brigade and General McClure, a regular of his command, of the 69th Brigade.

Opposite the 35th Division was the First Guard Division, perhaps the best in the German army, and the Second Landwehr, made up of men over thirty-five years old. Directly in front of the Americans were four well defined defensive lines; the Hindenburg line – in two parts; the Kriemhilde Stellung, perhaps stronger even than the Hindenburg line; and the unfinished Freya Stellung.

The attack was by column of brigades, the 69th Brigade leading, the two regiments in each Brigade, side by side, each with one battalion in the front line, one battalion in support and one battalion in reserve.

The artillery preparations began at 2:30 a.m., September 26th. On the afternoon previous the infantry had begun the move forward, and that night were up to the guns and awaiting the coming advance in the morning. After three hours of intense artillery preparation, the advance began at 5:30 a.m., and at the end of the day the men had captured Vauquois Hill, Cheppy Very, and had gone about half way between Varennes on the left and Charpentry on the right. About three miles had been about the net advance.

An advance was ordered for 5:30 a.m. next morning without artillery preparation, as the 60th Field Artillery Brigade of the 35th Division had been unable to get into position owing to the terrible condition of the ground over which they had to move and the lack of roads. The advance was begun at 5:30 but was shortly stopped, and the men ordered to dig in, and word sent back that no further advance could be made without artillery support. The total advance for the second day was about one-half mile, not including Charpentry and Baulny, and was made in the face of very great difficulties. The night of the second day found the 35th Division with an advance of two and one-half kilometres, in a total advance of seven and one-half kilometres; most of the advance having been made in the second attack about 5:30 on the first afternoon.

The morning of the third day was cold, with a fine rain in the air. At 6:30 in the morning the Germans counter attacked, but were driven back. The right of the line still maintained to a large degree its original formation, but there had been a great deal of intermingling between the 139th and the 137th Infantry on the left of the line, and the regimental commander of the 139th Infantry was behind the German lines on a most daring reconnaissance.

The attack was ordered for 6:30 in the morning and encountered severe machine-gun and shell fire, particularly from the Montrebeau Woods, which was a short distance north of Baulny. By this time the advance had turned slightly to the west, more or less following the bank of the Aire River. By night the men had secured a hold on the edge of the woods, but they were not in possession of it. A mile and a half had been attained by the end of that day’s operations.

On Sunday morning, September 30th, the division was ahead of the forces on either its right or left, and an attack had been ordered for 5:30 that morning. Moving slowly against very heavy artillery and machine-gun fire, the men slowly gained the crest of the slope which looks down into Exermont. An attempt was made to take it, but on account of the intense shelling and machine-gun fire, it failed. Colonel Clad Hamilton, of Topeka, commanding the 137th Infantry, was gassed and taken to the rear. Major Rieger carried his battalion almost a quarter of a mile north of Exermont reaching the edge of [the woods on Hill 240] but by this time their line was so thin due to losses, and the fire of the Germans was so heavy, that the commanding officers of the 139th and the 137th Infantry were ordered by Colonel Walker to fall back on Baulny Ridge, where the 110th Engineers were hurriedly preparing trenches and defenses. The men had to withdraw from Exermont and Montrebeau Wood, and retired to the heights of the Ridge. It is said that Captain Eustace Smith, known to his friends as “Red,” a lawyer of Hutchinson, was the last man to withdraw from Exermont.

Late in the afternoon of September 30th, after the Division had maintained the line to which it had withdrawn, orders were received for its relief by the First Division.

The total gain in ground by the 35th was ten kilometres, or six and one-fourth miles. Its farthest advance was three hundred meters north of Exermont, or to a point seven and three-quarters miles from the jumping-off place. Twelve German officers were captured, about nine hundred men, five six-inch Howitzers; three 77-milm. field pieces, and a number of other pieces of artillery.

After the relief took place the troops assembled in the vicinity of Charpentry, and were marched to a so-called rest camp near Vavincourt.

On October 14 to 15 the 35th Division relieved the French Fifteenth D. I. C. on the Sommedieue sector, near Verdun, and Dead Man’s Hill, which was a very welcome relief after the fierce days of the Argonne.

On November 1st the Division passed under the 17th Army Corps of the French Army, and several days later was relieved by the 81st Division, and attached to the Third American Army Corps. The night of November 6th was the last day the 35th Division spent in the trenches or under fire.

On November 9th and 10th the 35th Division passed from the Third Corps and the First Army, and entered the Fourth Corps of the Second American Army, under the command of Lieutenant-General Bullard. The Second Army was just about to make a great offensive east of Metz when the Armistice was signed.

The division after some weeks in the Le Mans area returned to America about April 23, 1919, leaving behind about 1,500 dead and with 10,605 replacements. Practically all of the units paraded both in Kansas and Missouri, and were demobilized and discharged in about three days at Camp Funston. The official report shows that there were some 1,480 deaths; 6,001 wounded, and 167 captured, making a grant total of 7,913 men. This loss, while not an excessive one, was mostly sustained in the one battle of the Argonne, where the losses were heavy.

Some of the division’s friends made the mistake of assailing the War Department for the casualties which the Division sustained. It may well be and is probable that the division did not have the best leadership possible and that it could have done its job with fewer casualties if its leadership had been different, but certainly the Division, itself, has no cause to be ashamed of its achievements, or of the gallantry of its officers and men.

(Reprinted from Connelley, William E. History of Kansas: State and People, Volume II; Chicago: The American Historical Society (1928), pp. 889-893. Transcribed by Bryce Benedict.)

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

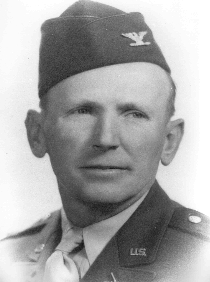

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

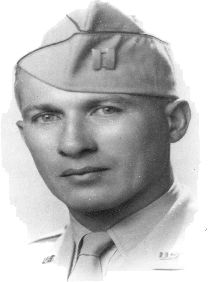

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

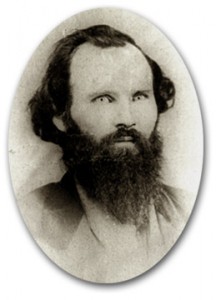

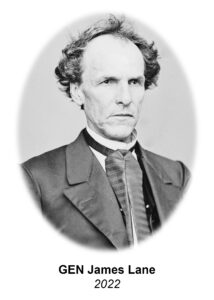

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

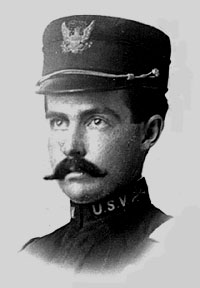

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

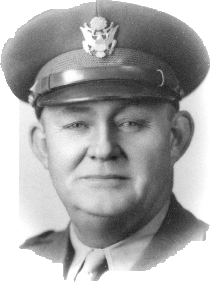

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.