The Jayhawk Squadron 1941-1945 introduction

In the spring of 1981 the National Guard Bureau requested that the 102d Military History Detachment, Kansas Army National Guard, write a history of the 127th Observation Squadron, a rather unknown (from the standpoint of our records) National Guard squadron from the period of World War II. Upon checking the general and special orders of the Adjutant General’s Department, it was quickly discovered that one scant document, the order placing the squadron in federal service, existed. Hence the project seemed of particular significance for the Kansas National Guard, considering the fact that the 127th was the second air squadron in the Kansas National Guard before the creation of the Air National Guard.

With the assistance of Chief Master Sergeant Melvin O. Simpson, Kansas Air National Guard, some of the unpublished monthly historical reports compiled by the squadron were located. A few of the reports had been combined with unpublished histories while others existed as the original monthly reports. These fragments were supplemented by additional monthly reports obtained from the Albert Simpson Historical Research Center, Maxwell Air Force Base. This base of information supplemented by oral history interviews, Wichita newspapers from the period, and documents from the National Archives have permitted an accurate squadron history.

The Detachment members would like to thank the former members of the squadron who have assisted us with the project. In addition, we would like to thank Charles Shaunessey, Archivist with the National Archives, and member of the District of Columbia Army National Guard, for the very important assistance he gave to this project.

The Jayhawk Squadron

The Adjutant General of Kansas received word on June 17, 1940, that the Army Appropriation Bill for Fiscal Year 1941 provided for the organization of five anti-aircraft regiments and eight observation squadrons within the National Guard. Through this bill the National Guard would increase its strength by 4,700 men plus enter the ever-expanding air side of the United States Armed Services. The creation of the five anti-aircraft regiments did not pose any major problems for the Guard since the plan called for the conversion of some of the existing non-divisional infantry regiments in the Guard to anti-aircraft regiments. Organizing air observation squadrons, however, was an entirely different matter. An air squadron required armory and hangar facilities prior to federal recognition, a substantial outlay of funds.

The National Guard Bureau surveyed the Adjutants General of several states and determined that the District of Columbia, Louisiana, Oregon, Iowa, and Oklahoma had adequate facilities for an air squadron in addition to the desire to organize such a unit. These states and the District were authorized squadrons without any changes. The Bureau recommended, however, that three additional squadrons be authorized for Wisconsin, Kansas, and Georgia as soon as facilities became available. While some of the states previously listed lacked enthusiasm about such a proposal or did not have sufficient facilities for a squadron, Kansas desired a National Guard air unit.

While the National Guard Bureau originally sought to establish observation squadrons in the mentioned states, the plan was soon expanded to establish pursuit squadrons as well. Both the terms pursuit and observation are unfamiliar today since they are taken from the aviation experiences of World War I and were replaced with current teminology in the early part of World War II. Pursuit squadrons became fighter squadrons, a designation they hold today. Observation squadrons, whose mission was to observe and photograph enemy troop activities, ultimately became photo and reconnaissance units or, as with the Kansas unit, liaison squadrons.

Recognizing Kansas’s potential, an air representative of the Bureau made a personal visit to Kansas City, Kansas on June 19, 1940, for the purpose of determining the suitability of that city for a pursuit unit. It was quickly detemined that a shortage of qualified pilots would make Kansas unsuitable for a pursuit squadron. Major General John F. Williams felt that National Guard pursuit squadrons should have pilots that were graduates of the Army Air Corps Training Center. Pilots with such training were simply not available in the Kansas City area.

As a result, plans continued through the remainder of 1940 to establish a National Guard observation squadron in Kansas. It was recognized that both Kansas City and Wichita potentially had facilities for the squadron. When it was announced that Kansas would receive a National Guard observation squadron both cities began competing for the unit. Kansas City hoped to get the squadron and house it at the Fairfax Airport. Though Kansas City had good facilities and more than adequate manpower to draw from, the Kansas City airport was owned by the Union Pacific Railroad. In order for Kansas City to be eligible for the squadron, it would have to arrange for a long term lease and then enlarge the runway.

Wichita, however, had the necessary facilities and initiated a very active campaign to secure the squadron for that city. For example, a party of Wichita leaders flew to Topeka July 31, 1940, and conferred with Govenor Payne Ratner and Adjutant General Milton R. McLean, urging them to designate Wichita as the site for organization of the squadron. A. S. Swenson, Chairman of the Wichita Chamber of Commerce, noted that the power to designate the site was within the hands of the Governor and the Adjutant General acting on the advice of the State’s Military Board. While the fact that Major General John Williams, Chief of the National Guard Bureau and a Missouri native, at first favored Kansas City receiving the squadron, ultimately the Governor and the Adjutant General chose Wichita. Significant factors in Wichita receiving the squadron included the substantial pool of pilots available in Wichita due to the CAA Pilot Training Center and in addition, the city’s overall role as a leader in civilian aviation. The rather healthy Chamber of Commerce campaign merely finalized the decision rather than causing Wichita to receive the squadron.

The squadron, according to the plans of the War Department, was tentatively planned for federal recognition on August 1, 1941, and for induction into federal service on October 15, 1941. In order for the squadron to receive federal recognition, however, it had to have 103 men. Therefore the first priority for the fledgling unit was to recruit the necessary number of men for recognition. [Editor’s note: following the outbreak of the war in Europe and the fall of France the Kansas National Guard was ordered into Federal service in December, 1940 for one year’s duty, for the purpose of training the division and enhancing national defense readiness. The 35th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit, and to which existing Kansas Guard units were assigned, was sent to Camp Robinson, Arkansas. The one year of duty was turned into five with the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.]

Considering the mission at hand it was quite fortunate that Paul N. Flanary was a Wichita resident. Flanary held a commission in the Air Corps Reserve as a first lieutenant and was an official in the CAA program in Wichita. In this capacity he gave flight instruction to a substantial number of area residents. Lieutenant Paul Flanary was appointed Commander of the 127th Observation Squadron May 24, 1941. With his appointment order was the authorization to recruit the squadron. Since he had given flight instruction in the area, Flanary immediately contacted a number of his present and former students, asking them to join the new squadron. Don Hattan, at that time a Chevrolet field representative for General Motors, had taken pilot training from Flanary and upon the latter’s contact joined the squadron as an enlisted man. Flanary is even today remembered as an extremely fine officer with a good deal of personal charm. As the squadron was organizing, Flanary and his wife threw parties every few weeks for the squadron membership, making no distinction between officers and enlisted personnel.

To give an illustration of his recruiting powers, while the unit was organizing Flanary heard that the Isham Jones Orchestra was scheduled to play a dance in Wichita. He invited the entire squadron to the dance. During the course of the evening Flanary began to talk to a couple members of the band. His comments on the new squadron so intrugued Lenny Hartzell, the trumpet player, and Tony Markantonio, that they left the orchestra, stayed in Wichita and joined the 127th Observation Squadron.

Flanary was highly successful as the squadron’s head recruiter. By early August 1941, the new air squadron had 115 men in its ranks. It was, however, still short of officers since it only had nine officers but was authorized a total of thirty-one. Officer requirements were somewhat stringent since to be commissioned as an officer pilot a man had to have 300 hours of flying time and 100 hours of this had to be spent in planes with over 200 horsepower engines. Officer Observers were required to have some technical skill such as photography, radio operation, armament, or engineering. Despite the unfilled officer slots, the squadron had more than the requisite 103 men, and was ready for its inspection, in preparation for federal recognition.

When the squadron was inspected, August 4, 1941, it had a total of 125 men. The inspection was made by Colonel Jasper K. McDuffie, the unit’s advisor, instructor, and officer representing the Kansas Adjutant General. On August 4 federal recognition was given and the men were sworn into state service. The squadron was due to be ordered into active service some time in October 1941. In the meantime, the unit trained every Monday evening at the municipal airport. Originally, the unit trained at the Wichita National Guard Armory but, considering the 127th’s mission, it was quickly moved to the municipal airport where tents had been erected for squadron menbers. With the assistance of Sergeant E. W. Worthen, a Regular Army non-commissioned officer (NCO), squadron members received their first training in close order drill. Even while plans were being made for active duty, Wichita was preparing facilities for the squadron’s eventual return. Newspaper reports described the progress of the $304,000 hangar and armory designed for the squadron, located on the east edge of the Wichita Municipal Airport.

Active duty came, however, before the 127th could use their new facilities. The Adjutant General of Kansas, Major General Milton R. McLean, through General Order Number 101, informed the squadron that it would be inducted into federal service on October 6, 1941. Hence, the 127th became the last Kansas National Guard unit organized before World War II and the last Kansas unit to enter federal service. According to the plan devised by the War Department, the squadron was to entrain for Fort Leavenworth on October 13, 1941. It would remain there and take training at Sherman Field until facilities were ready at Brownwood, Texas, where it would be permanently based for the duration of the “emergency.” At 6:00 a.m. October 13, 1941, all officers and men had breakfast at Wolf’s Cafeteria and then went directly to the Missouri Pacific depot where a special train was waiting to take them to fort Leavenworth. The squadron had already received three planes, a Douglas O-47A, a North American BE-1A and a Douglas O-38E. These planes were flown to Sherman Field by Major Flanary, Lieutenant Glenn Miller and Lieutenant Kenneth Roney.

The departure of the squadron was distinguished by the farewell breakfast. Colonel J. K. McDuffie and Master Sergeant E. W. Worthen, both of whom helped with the unit’s training, were the guests of honor. Both were honored by the squadron with gifts in appreciation for their assistance. The Wichita Chamber of Commerce, so active in promoting Wichita as a site for the squadron, gave a program Monday morning and presented several hundred dollars to be used for the benefit and comfort of the squadron members. Once this was done, the special train consisting of three coaches and two baggage cars left the Missouri Pacific depot.

Shortly before it departed, the squadron members, together with a committee appointed by a civic organization in Wichita, reviewed a total of eighty-five designs for the squadron insignia. Ultimately the design chosen was proposed by Major Flanary to the Adjutant General who concurred and forwarded the design to the Chief of the National Guard Bureau. According to Major Flanary:

“The Jayhawk represents the State of Kansas since the state is known as the Jayhawk State. The bird perched atop the clouds indicates aviation and being in the air which applies to this squadron. Also, the presence of helmet and goggles adds to this impression. The observation angle is indicated by the binoculars hung around his neck.”

The design indicated that the squadron was a Kansas unit and intended to carry this distinction clearly on its aircraft.

The War Department did not appreciate the novel design submitted by Major Flanary, stating “The Jayhawk in the design looks too much like a pelican which is used in the crest for organizations of the Louisiana National Guard.” Instead Major Lyle Clough of the War Department staff proposed:

“On and over a blue disc edged in black with a cloud issuing from base, a blue, white and black falcon, yellow beak and feet, with wings outstretched, wearing an orange aviator’s helmet, with a pair of orange binoculars hung on its breast.”

When Major Flanary insisted on consideration of a Kansas design with the mythical Kansas bird, the reply from the War Department was somewhat caustic:

“In addition to the similarity of the form of the beak to the pelican used in the crest for organizations of the Louisiana National Guard, the sly invitational caricatured ‘Mother Hubbard’-like appearance, the countenance, indicating lack of skill, certainly is not representative of the personnel of the organization nor of their functions. Funny, fantastic designs may be amusing at first sight, but they do not have a permanent value. In view of this the original design submitted by the squadron is not considered suitable.”

Ultimately, the original Kansas design was accepted, and was utilized by the squadron and its wartime succesors throughout the Second World War.

Since the organizational phase of the squadron was completed, training began in earnest with the squadron’s 200 mile move to Ft. Leavenworth. They arrived at the Fort on October 13, 1941 at 3:45 p.m. and located their new quarters. At Ft. Leavenworth the squadron was quartered in a regular barracks facility, a full four miles from Sherman Field where the aircraft were to be hangared. At Ft. Leavenworth, the men received their full initiation into the service, to include basic training, a full battery of Army shots, and classification exams which assisted the Army in placing the soldiers in the field in which they exhibited the greatest aptitude. The basic training, the aptitude tests and even the shots were preparatory to the major role of the squadron, flying.

Major Flanary took the squadron to Sherman Field where they viewed the aircraft available for the unit. By November of 1941 the squadron had one BE-1, one O-47A, one O-38E and several L-1’s. All of the aircraft were single engine observation/liaison planes. Through November and December 1941 flight practice and instruction was given, and equally important, the squadron’s mechanics were trained. The new mechanics were placed under the supervision of Master Sergeant Charles M. Dauster and Technical Sergeant Schuyler Shore, both experienced aviation mechanics. They required the squadron’s novices to begin their training with such mundane chores as washing planes until they had received sufficient instruction to be full-fledged mechanics.

From November of 1941 until the spring of 1942 the squadron continued to take shape as an effective fighting organization. Major Flanary, who had originally taught a number of the pilots to fly, was rightfully proud of the squadron. Occasionally, however, they did cause him some difficulties. For example, some of the pilots in the course of their training flights left Sherman Field and flew under the river bridge at Atchison, Kansas to prove their flying skills. One pilot “skimming” the Missouri River caught his landing gear in the water and tipped over the plane. When finally recovered, it had nine tons of sand in it. These stunts caused some of the squadron pilots to be relieved from duty but, due to the demand for skilled pilots, they were ultimately reinstated and were allowed to fly again.

It was not until February 10, 1942, that the squadron had its first major training accident, resulting in fatalities. On that day a BE-1A piloted by Second Lieutenant Boyd V. Mann with Second Lieutenant Norman Meeks as the observer, crashed near Blue Springs, Missouri at 4:30 p.m. The accident report simply stated “cause of the accident unknown.”

Despite such setbacks the squadron continued to build in strength. On March 22, 1942, the 127th received its first L-4’s (or Piper Cubs), a total shipment of 12 aircraft. Most of the squadron’s pilots were officers. This is not to say, however, that some enlisted men were not qualified for flight duty. For example, Sergeant Spiva, one of the squadron’s parachute riggers, was an acrobatic pilot and had been a “wing walker.” He had learned to fly during the Thirties and performed all over the Midwest. Within the squadron he was perhaps best known (from his civilian days) for one of his acts of standing on the wing of a biplane while it was in flight. He did not, however, pilot a plane for the 127th but rigged parachutes and trained many others to master this skill. Don Hattan, mentioned earlier in this history, was also a trained pilot, having taken his instruction from Major Flaanry in the CAA program.

Shortly before the squadron left Fort Leavenworth for its new base in Tennessee, the squadron had its second major training accident. The squadron’s O-38E, piloted by Lieutenant Harold Chandler with Private Forest Wilson serving as observer, crashed and burned across the Missouri River. Aside from this accident and the mishaps previously mentioned, the squadron had an extremely good safety record, in terms of loss of trained personnel.

Having completed the first phase of its training at Sherman field, the squadron was ordered to report to Tullahoma, Tennessee, leaving Ft. Leavenworth April 12, 1942. According to the original plans, the squadron was to be based at Brownwood, Texas until the “emergency” was over and it could return to its home base at Wichita. The December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed all plans for American military units. A number of 127th personnel were off the base that Sunday (December 7) and returned to find it almost impossible to get back on base. The war had come to the United States and with it, war time security.

The move to Tullahoma proceeded according to plan during the month of April, 1942. Naturally, as an air squadron, the change in base was two-phased with the planes being flown to the new base by the qualified pilots and the equipment and ground personnel traveling by train. The move was accomplished without any mishaps although the ground personnel found one portion of their trip worthy of note. When the train reached Hope, Arkansas, the squadron members were welcomed to the community and after some discussion city officials, recognizing that most soldiers enjoy a good party, opened the evidence vault for their enjoyment. The vault was well-stocked with contraband liquor and although one official requested the guardsmen to “leave some evidence,” it is doubtful that much was left.

As a further complication, several men developed symptoms of measles during the trip and the train was in essence quarantined for the remainder of the trip. When the train reached Tullahoma they were met by ambulance but since the measles epidemic had never transpired, the ambulances were not required.

As the squadron changed bases other changes were also occurring. Originally a high percentage of the squadron came from Wichita and surrounding communities like Mount Hope, Andale, Colwich, Garden Plain and Saint Joe. According to one former member, there were only about a dozen people in the original squadron who weren’t from that immediate area. After the squadron reached Sherman Field in October of 1941 it began experiencing changes in personnel. For example, before the year was out, there were a number of officers transferred into the squadron from other military organizations. Some members of the squadron chose to leave the unit for officer candidate school (OCS). Major Flanary apparently encouraged the upward mobility of his personnel. For example, in February of 1942, he approached Staff Sergeant Don Hattan and asked him if he would like to attend OCS. Hattan was a commissioned officer by May 30, 1942. The gradual change of the squadron’s personnel is clearly shown through the rosters in the appendix. [Editor’s note: the appendix has not been included]

In addition to the personnel changing in early 1942, the squadron had the first of many name changes. On January 13, 1942, it was redesignated as the 127th Observation Squadron (Light) but was again redesignated as the 127th Observation Squadron on July 4, 1942. Despite the changes in name and in personnel the sqaudron’s mission remained essentially the same and it was still essentially a Kansas National Guard squadron.

Tullahoma, Tennessee, was a distinct shock for the squadron. The most obvious problem they faced was the virtual lack of facilities. Tullahoma Army Air Base was still under construction when the 127th arrived. For example, the Post Exchange (PX) was a wagon on wheels. Ultimately barracks were finished but not before the squadron had undergone a good deal of inconvenience. The 127th was not the only military organization stationed in the area. Tullahoma Army Air Base was situated in close proximity to Camp Forrest, Tennessee, the site of a major infantry center. The Army’s 33d Division was stationed on the other side of the base, a factor which frequently caused some difficulty. Due to the already existing rivalry between air corps personnel and the rest of the Army, 127th members went into town in groups rather than as individuals. It was by far safer that way.

Nonetheless, the squadron continued with the business at hand, training for its wartime mission. They regularly engaged in training flights, marched, and received instruction in military courtesy. Frequently, despite the off-duty rivalry, they trained on missions cooperating with the 33d and 80th Infantry divisions, both of which were stationed in the vicinity. At the same time the 124th Observation Squadron from the Iowa National Guard was stationed at Tullahoma. Beginning in 1942, the squadron was assigned to the 75th Observation Group (headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama) for its higher headquarters. This affiliation would continue until August 19, 1943, when the squadron was transferred to the First Air Support Command, Morris Field, Charlotte, North Carolina.

As is perhaps true with any military organization in wartime, by 1942-43 the squadron was evolving into a different organization in terms of mission, and too, personnel. To illustrate this, squadron records from that period cite the completion of training of the first liaison pilots, April 12, 1943. As described by former members, the liaison mission was rather ill defined but it included tactical reconaissance (including aerial photography), artillery spotting, the pick-up and delivery of messages between field units, the transportation of personnel, and the evacuation of wounded from the rear areas behind the actual battlefield. While at Tullahoma the squadron trained liaison pilots from its own ranks and trained pilots for this mission who were ultimately assigned to other squadrons. Its redesignation to 127th Liaison Squadron officially came April 2, 1943. The squadron’s records clearly indicate the squadron’s training function and the gradual loss of original personnel by the announcement that on April 12, 1943, the first group of liaison pilots trained by the 127th were ordered to overseas duty. According to the 1943 squadron history, non-rated liaison pilots were attached to the squadron every few weeks. After training with the 127th these pilots were shipped directly overseas.

One other major training activity in which the 127th was engaged while based in Tullahoma was the Louisiana Maneuvers. The squadron left Tullahoma on September 5, 1942, for Shreveport, Louisiana to participate in the largest war games ever staged by the United States Army. During the Louisiana Maneuvers the 127th worked in close cooperation with their higher headquarters, the 75th Observation Group. This was perhaps the closest training activity which could simulate the squadron’s wartime mission. The maneuver exercises were scheduled in periods of three days duration with two day intervals in between. The squadron’s personnel for the first time wrestled with the problems of a wartime existence. They had to move with their assigned force, the “Blue” army, supply men and aircraft, camouflage their facilities and fly scores of hours as the “eyes” of the Blue force.

This was followed by the squadron moving, October 12, 1942, to De Ridder, Louisiana for more maneuvers. Utilizing their very effective O-47’s and the versatile L4’s, “Jayhawk” squadron pilots flew over large areas of Louisiana and even into Texas. In addition to the aircraft already mentioned, the squadron utilized P-40’s and A-20’s for their work with the ground troops. Once the maneuvers were completed, squadron members prepared for furloughs, a well-deserved rest after an extremely hectic flight schedule.

The 127th was stationed at Tullahoma longer than any other base in its wartime existence. It remained at Tullahoma from mid-April, 1942 until mid-October, 1943, a total of 18 months. On August 19, 1943, the 127th was reassigned to the First Air Support Command (headquarters at Morris Field, Charlotte, North Carolina). This command would soon become the First Tactical Air Division.

While there were a number of Kansas Guardsmen in the squadron for the first year at Tullahoma, on August 11, 1943, there was apparently a major reorganization within the Air Corps which would result in the loss of a large number of enlisted personnel, including the skilled and trained section heads to the higher headquarters, the 75th Observation Group. The transfer of Kansas personnel to other squadrons both in the United States and overseas actually caused the 127th to lose the majority of its Kansas personnel. One former member estimated that as early as April of 1943 only thirty-five to forty percent of the original Kansas squadron remained. The personnel changes of August, 1943 reduced that percentage considerably. According to Colonel Anthony Leis (Retired) the squadron members were promised they could stay together as an identifiable Kansas squadron. Apparently, however, wartime priorities required a different policy. Major Flanary was replaced in command by Captain John B. Noble on August 29, 1943. Nonetheless, a small Kansas contingent would be with the squadron throughout the war and the Jayhawk insignia would be utilized until the squadron was deactivated on November 15, 1945.

Beginning September 1, 1943, the 127th entered what seemed to be a year of constant change and reassignment. They accomplished their move to Morris Field in Charlotte, North Carolina, the headquarters of the First Tactical Air Division, in September. Since they were located at division headquarters the squadron found their accomodations and supply facilities to be far superior to the ones at Tullahoma. Within two weeks of their arrival, for example, the squadron received a shipment of fifteen L-5 observation planes. The receipt of these planes called for another battery of training for the liaison pilots in order to familiarize the men with this new aircraft.

While at Morris Field a 127th squadron member became the first member of the so-called “Caterpillar Club.” Staff Sergeant Arthur M. Luedtke, flying a new L-5, lost his orientation and ran out of fuel. He had to “hit the silk” and spent a part of the night in a tree until a couple of youngsters found him. He was the first, though certainly not the last, 127th member to “hit the silk.”

Then on October 12, 1943, the squadron was again ordered to move, this time to Statesboro, Georgia. By truck, the 314 enlisted men and 18 officers changed bases. At Statesboro Army Air field the 127th’s mission was much the same as at Tullahoma, training liaison pilots. Their training at both bases was significant for several reasons. As an example, the liaison pilots trained by the squadron were flying NCO’s, not commissioned officers. By the time the squadron reached Statesboro it had already trained some one-hundred such flight crews of flying sergeants to do liaison work overseas. It is also significant that the training was not simply flight training. According to Lieutenant John B. Gaffield, squadron operations officer, the squadron’s mission was to take pilots from the civilian flying school and teach them to be competent Army pilots. These trainees were taught to be proficient in basic flight maneuvers, night flying, navigation, and to engage in military missions such as aerial photography, pick ups, drops, and recognition panels. Since March of 1943 the squadron had served as a replacement training unit, teaching pilots not only to fly but to do first echelon maintenance on their aircraft and to pull proper inspections. The purpose of this type of training was to permit the pilot to be able to operate in the field as a separate unit, when necessary.

The year 1944 found the 127th Observation Squadron still in the United States and still engaged in training. Despite continual stateside duties since 1941, the squadron’s morale was good. During the last week of January the squadron showed its patriotic spirit by involving itself in the fourth War Loan drive. Their quota was 20% of their pay and a contest was set up between the liaison pilots and the ground personnel. Regrettably subsequent reports fail to tell of the success or failure of this contest. A bit of life was added to the 127th’s routine by the organization of an N.C.O. Club at the Statesboro Army Air Base. The officers elected by the club were First Sergeant Hommertzheim, President; Technical Sergeant Leis, Vice-President; and Sergeant Wohltman, Secretary-Treasurer. Records indicate that all of these men were Kansans.

By this time, the men were showing signs of impatience since there was a genuine desire for some overseas duty. With this in mind, the squadron began accelerated training for its membership. For example, on January 28, 1944, the squadron began weekly hikes. On that particular day they hiked five miles in one hour with full field equipment.

Beginning in April of 1944 the squadron received indications that it would not remain a training organization much longer. In April, it was put on alert status and was given special training indicating possible overseas duty. A set of lectures were scheduled and instruction was given on survival methods in the tropics, the desert and the Arctic. This flurry of speculative activity was followed, on May 1, 1944, by the redesignation of the squadron as the 127th Liaison Squadron (Commando). This redesignation would be the last for their period of wartime service. The exact rationale for this redesignation is not evident from the available records.

While an overseas move seemed imminent in April, the excitement promoted by possible overseas assignment quickly died down when orders were not forthcoming. Instead, the squadron again was forced to go through a series of quick moves. Orders sent them to Aiken Army Air Field, South Carolina on May 18, 1944; Dunnellon Army Air Field, Florida on June 10, 1944; Cross City Army Air Field, Florida on June 21, 1944; Drew Army Air Field, Tampa, Florida on August 17, 1944; and Lakeland Army Air Field, Florida on August 22, 1944.

After four months of constantly being on the move, the squadron again had a few months to train and plan for whatever the future held for them. The possibility of overseas shipment still seemed likely but after the disappointment of the past six months, there was a good deal of uncertainty. Squadron members qualified on the .45 pistol and the M1 carbine on the 4th and 5th of September, and on the submachine gun on the 16th. Shortly thereafter, all nonessential records were destroyed and the squadron began to make final preparations for its departure, hopefully overseas. Orders were finally received for overseas duty in India, on October 23, 1944.

According to orders, the squadron proceeded by troop train from Florida to Camp Anza, California, arriving there on November 2, 1944. Temporary quarters were arranged for the men while supplies were obtained for the overseas trip. The squadron members again entrained on November 8, 1944, for the Port of Los Angeles where the squadron and its equipment were loaded aboard the USS General John Pope. The 127th was designated as an advance detail to the ship and was to serve in a guard capacity throughout the journey. The loading of the vessel was completed within two days, and on November 10, 1944, three years after mobilization, the squadron left the United States for overseas duty in a combat theater.

After the customary sea sickness, the passengers of the ship settled down to life in their temporary “home.” Land was not again sighted until November 26, 1944. The men sought diversions to pass the time on the lengthy sea journey. For example, they organized their own orchestra and had various concerts and talent contests to amuse themselves. One highlight was the crossing of the equator in mid-November. As was traditional, initiation rites were scheduled for those who had not previously crossed the equator. Members from various military units elected representatives to participate in the pollywog ceremonies and at the conclusion, all members of the squadron were hardened shellbacks.

The land sighted on November 26 was Australia and as the ship put into Melbourne harbor all hoped for at least several hours of shore leave to again feel solid earth under their feet. This did not occur. On November 29, the ship’s voyage was resumed, finally docking at Bombay, India on December 10, 1944; American currency had already been exchanged on board for Indian currency. The squadron members remained with the ship until December 13 when they departed by train for their base called Kalaikunda. It was an extremely rough three day ride to reach this base camp located near the Indian city of Kharagpur. This placed their base roughly eighty miles from the city of Calcutta. Once they had reached the base and made their quarters liveable, the flying personnel began logging hours of flight time to regain their touch for flying after a several month lapse due to their long trip from Florida to India.

In many respects the first month of overseas assignment seemed rather uneventful. The month of January, 1945 was spent on orientation activities including medical shots, dental survey, and orientation and training lectures. The squadron’s aerial arsenal was increased with the addition of two C-64’s from Karachi, India. For its wartime mission, the squadron was subdivided into four flights, the “A” flight commanded by Lieutenant Fred Crisman, “B” flight by Lieutenant John Gaffield (who had served as the squadron’s historian), “C” flight by Second Lieutenant D. L. Carter, and “D” flight by Second Lieutenant J. J. Hoose.

“B” flight was selected in February of 1945 to operate in cooperation with British ground forces in the third Arakan campaign into Burma, beginning on the 21st of that month. For the next thirty days, squadron pilots were constantly involved in duties supporting the British Army. Their missions included such activities as photographic and reconnaissance duties, evacuation of wounded, supply drops, courier duties, and cargo flights. They were entrusted with secret messages, regular mail and with transporting fresh blood to the front. Their operations were directed from the Tactical Air Command headquarters of the Fifteenth Corps of the British Army (their actual higher headquarters in this period was the Second Air Commando Group, United States Army Air Corps). Royal Air Force intelligence kept them apprised of the situation and their actual liaison work was directed through Captain York, Royal Air Force.

On the first day of the offensive the squadron operated out of Cox’s Bazaar, Burma, but orders moved them to Akyab Island, Burma to a British fighter strip. During the offensive “B” flight was constantly changing bases in order to remain in close proximity to the front lines. After the assignment to Akyab Island, the squadron moved to Ramree Island, Kysbon, and then finally on eastward into the mountainous regions of Burma where they flew in support of the 32d West African Division. Although they flew unarmed planes and did not engage in direct combat with the Japanese, their duties were not without danger. For a brief period they flew out of Kyaukpu, then virtually the only piece of ground in that area in Allied hands. The field was subject to sniper fire and had been seeded with boobytraps by the Japanese who still controlled the surrounding jungle.

According to the squadron’s records, “B” flight logged in more than 1,500 flights with only three regarded as unsuccessful. The three unsuccessful flights resulted in crash landings, two of which had casualty passengers aboard. In all three cases the casualty passengers survived as did the pilots. Squadron pilots distinguished themselves on a number of occasions with their sense of duty to their injured passengers. On one occasion a pilot, transporting a West African causalty, demolished his aircraft in a jungle crash landing. He used parts from the wrecked plane and built a two-wheel cart to transport his casualty to safety.

Occasionally the squadron was called upon to transport important persons in the combat zone. Lieutenant General Sir Phillip Christison, Commander of the British Fifteenth Corps, utilized the squadron on a number of instances. Lady Louis Mountbatten, wife of the Supreme Allied Commander, flew in a 127th aircraft in an inspection tour of the forward area hospitals and casualty clearing stations. This tour was a result of her status as a General Officer in the British Queen’s Ambulance Corps.

In many respects the first major disaster for the squadron occurred at the hands of “mother nature,” rather than the Japanese. On March 12, 1945, the winds of a tropical storm lashed the base of the squadron detachment. From 7:00 to 7:45 p.m., the base suffered from the tropical winds; when the storm had passed, every aircraft on the field was either condemned or destroyed. Only four planes, which were away on a mission, survived that storm. The 127th personnel escaped without injury but others on the base were not so furtunate. Eight members of another squadron were killed and more than one hundred Air Corps personnel were injured. As the historical officer recorded, “the entire Japanese Air Force striking simultaneously couldn’t have done a better job.” Following the storm a service unit was moved in and the repair and reconditioning of the aircraft began. The end of March found the squadron’s usable aircraft restored and back on the flight line, and the living quarters were, by and large, restored to their pre-storm condition.

The 127th Liaison Squadron (Commando) cooperated with the British Army from the beginning of the Burma offensive in February until the latter part of April, 1945. Through this campaign, every pilot that participated (with one exception) flew sufficient hours and missions to entitle him to an Air Medal with one Oak Leaf Cluster, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and most of the pilots were eligible for a second Oak Leaf Cluster to the Air Medal. Above all, this campaign proved the value of a light plane such as the L-5 in a jungle environment engaging in communications work and transporting men and materials.

On May 1, the British offensive again picked up it pace with the occupation of Rangoon, Burma. The British campaign in Burma officially ceased on May 6, 1945, and with the collapse of the Japanese defenses the 127th received a well-earned rest. Beginning on May 17, the L-5’s of the squadron were flown back to their original base in India. The move of men and equipment had been completed by May 22, 1945.

Though the war in the India-Burma theater seemed to be nearing a successful conclusion, the 127th still had significant missions to accomplish. In June of 1945 a thirty plane flight left from Kalaikunda Army Air Field, flying over the “hump,” with Kunming, China as a destination. Ten planes from the 127th were among the thirty, complete with their pilots, who served as ferry pilots. During that month, 25 L-5 aircraft were transferred from the organization to higher priority organizations on the China-Burma-India theater. At the end of the month the organization was still functioning with a total personnel strength of fourteen officers and sixty-six enlisted men.

Since the combat theater had shifted away from the base area of the 127th a change in base seemed imminent. July passed with little in the way of outstanding occurrences and certainly nothing in the way of combat missions. Finally, on July 29, the squadron was placed on a twenty-four hour alert, effective August 3, 1945. The equipment was packed and shipped to Calcutta, India, with the personnel to follow on August 4, 1945. The traditional military rumor mill indicated the squadron would perhaps be home by Christmas.

The rumor mill was not entirely wrong. The men boarded the USS General Collins at Calcutta and departed on August 7, 1945 for an unknown destination. The remainder of the month was spent on board ship in the Pacific Ocean; while they were at sea the war ended. On or about September 15, 1945, the squadron reached its destination, Okinawa. According to Kansas National Guard records the 127th was shipped out of India for the express purpose of participating in the invasion of Japan. With the war over, the men took temporary quarters on Okinawa and waited impatiently for new orders. The three week wait plus a diet of “C” rations was not conducive to the squadron’s morale.

Orders were finally received which transferred the 127th ground personnel to the 25th Liaison Squadron stationed on Mindanao, Philippines. The liaison pilots an officers were transferred to various units on Okinawa. Before much reorganization could occur, new orders were cut dated October 29, 1945, inactivating the squadron effective November 15, 1945. Hence, Yontan Air Strip, Okinawa became the last base of the squadron for all practical purposes.

Now inactivated, the personnel were placed aboard a converted freighter which was to return them to the United States. The men slept in the holds where makeshift beds, constructed of two-by-fours and Army canvas, were their scant comfort. The ship proceeded north and picked up the Japanese trade waters to gain speed back to the United States. The northern route, however, proved to be so cold that the men could not take baths for two weeks. When they entered San Francisco harbor after thirty-two days at sea, they were, according to one former member, “a dirty filthy bunch.” Ironically, San Francisco offered little more comfort because upon arrival the remnants of the squadron were quartered on the beach in twelve-man tents. That night the winds blew most of the tents away. This hardly seemed a fitting conclusion for a squadron which had served four years of active duty.

Of the original squadron only four Kansas men were left: Technical Sergeant Larry M. Gormann; Technical Sergeant Anthony A. Leis; Staff Sergeant Paul L. Jacobs; and Staff Sergerant Albert Davis. Of this group one returned to the Kansas National Guard. When the 127th Fighter Squadron was organized in 1947, Anthony Leis joined the Kansas Air National Guard as a technician, serving with the Air Guard unit which was the direct descendant of the 127th Observation Squadron. Anthony Leis retired from the Kansas Air National Guard as a Colonel in the mid 1960’s.

The 127th Observation Squadron was a highly successful military unit. Granted, its term of overseas combat duty was of somewhat limited duration, but it did make a sound contribution to the war effort. For approximately two years, it served as a training squadron, training enlisted pilots in observation and liaison duties. Once sent into a combat zone, the caliber of pilots was very evident in terms of the successful missions flown by the personnel. It won praise from the British Army which found its services indispensible in the Burma campaign. It was both a credit to the Army Air Corps and, of course, to the Kansas National Guard.

Prepared by the 102d Military History Detachment, Kansas Army National Guard; Topeka, Kansas, 24 January 1982 (transcribed from the original and edited by Bryce Benedict)

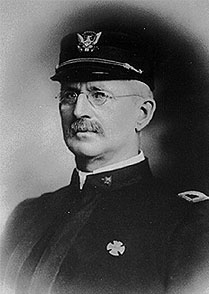

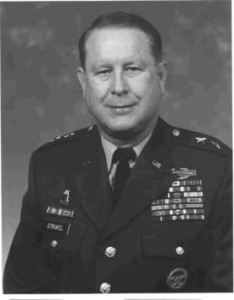

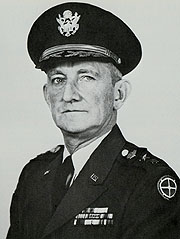

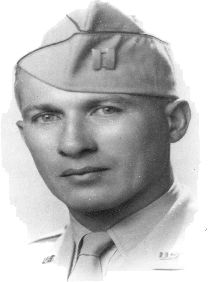

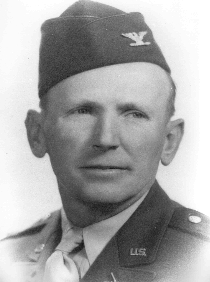

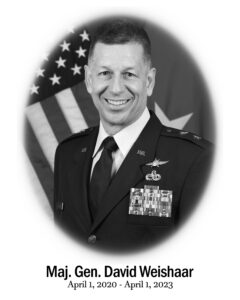

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

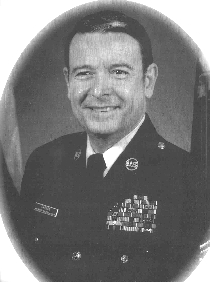

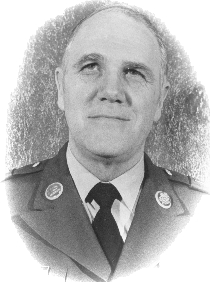

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

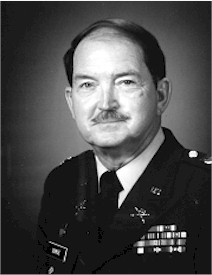

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

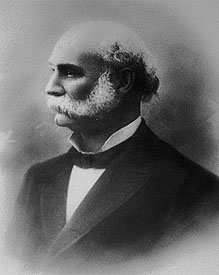

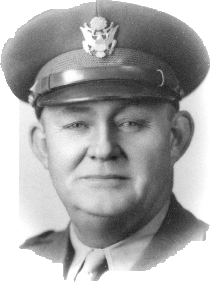

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

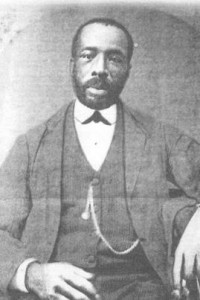

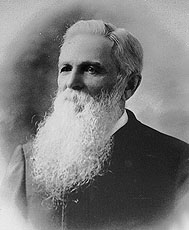

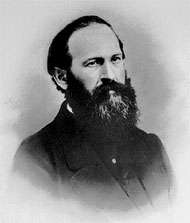

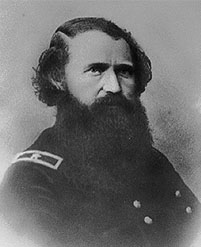

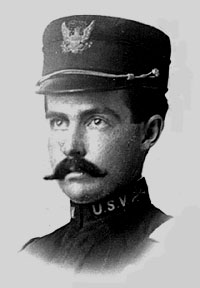

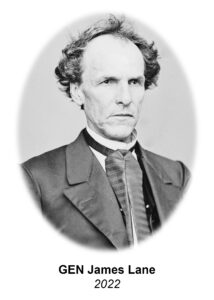

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

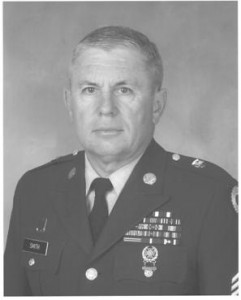

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.