A little over 100 years ago, on Nov. 11, 1919, the Kansas State Guard quietly went out of existence. It had performed valuable service during World War I, but today few people know it ever existed.

Most Kansans supported the war effort. Thousands volunteered for military service. Civilians supported the war by making donations to the Red Cross and buying Liberty Bonds, by making and donating clothing items for soldi’ers and by conserving food and fuel. Some Kansans further demonstrated their patriotism by ostracizing and verbally and physically abusing neighbors who failed to subscribe to Liberty loans, who failed to salute the flag or who spoke against the war.

Partly due to a fear that German agents would commit acts of sabotage within Kansas, the Home Guard was created in June 1917. The Home Guard was a cross between a civic club and a sheriff’s posse. Each Home Guard company was to be governed through bylaws, one of which provided that the object of each company “…shall be to promote, develop and foster loyalty and patriotism for flag and country; to furnish elementary military training and knowledge to its members for the purpose of enabling them to render service in defense of the country if called upon to do so, and to aid and assist in the relief of the families of those engaged in the federal military service, and to raise and distribute funds for these purposes.”

Eventually, over 150 Home Guard companies were organized. The men were given no pay or other compensation and were not provided uniforms or weapons, except that in August the state distributed 500 obsolete single-shot rifles among the companies. Some Home Guards performed guard duty at several civilian manufacturers, but otherwise there is little evidence that the Home Guard did much of anything, although some of its members benefited from having received some basic military education before being inducted into the service.

In August 1917, the entire Kansas National Guard was mustered into the service of the United States. This created a military vacuum within the state and one that was not being filled by the Home Guard. On February 15, 1918, Gov. Arthur Capper, by executive order, abolished the Home Guard and created the Kansas State Guard. In addition to being subject to the control of The Adjutant General, the State Guard could also be mobilized as an emergency “constabulary force” and, when mobilized, could be required to serve anywhere in the state.

The more disciplined State Guard did not appeal to many of the Home Guards and they did not join it. However, the State Guard was popular and eventually 281 companies were organized, each with an average of 65 men. Included among these companies were seven companies of Blacks in Independence, Kansas City, Lawrence, Coffeyville and Topeka.

Like the Home Guard, the members of the State Guard served without compensation and provided their own uniforms. Often the local community would contribute funds for the purchase of uniforms, but if someone hesitated to donate, an implied threat coupled with public scorn would often lead to a change of heart by the reluctant donor. Weapons were neither provided nor authorized. A few State Guard companies were issued rifles, but once it was discovered that the weapons were not being properly cared for it was decided not to issue any more.

The State Guard was a segregated institution, as was the Army and most of society. Blacks had not been allowed into the Kansas National Guard, but they were allowed to form seven State Guard companies. These companies performed the same type of duties as did the white ones. In Topeka, Black soldiers visiting town from Camp Funston were denied access to the YMCA, so Topeka’s Black State Guard company opened a YMCA for Black soldiers.

According to its official history, “The activities of the State Guard were confined to participation in weekly drills, patriotic parades, assistance in Liberty Loan, Red Cross and kindred ‘drives,’ instruction of men anticipating early induction into the army and, in a few cases, to the furnishing of guard details for property protection.”

After the war, most of the companies made reports summarizing their activities. The report of a company from Lawrence is typical:

Participated in all four Liberty loan drives, and acted as escort to all contingents called into service. Performed guard duty at Kansas University at time of fire at Fowler shops for a period of two days. Acted as funeral escort five times at burial of deceased soldiers sent home for burial; furnished firing squad six times at funerals under military, honors. Performed guard duty at bridge when called upon by local authorities on Kansas River bridge.

Besides helping to rouse support for the war, the State Guard also acted to suppress disloyalty at home. During the war “…loyalty was measured by what a person said and what he did to promote the war effort. People who did not contribute to various war funds, buy bonds, conserve and produce food, join the country’s armed forces, if eligible, and participate in various patriotic organizations were often branded as disloyal or pro-German.”

The post-war reports of the companies provide numerous examples of the suppression of alleged disloyalty:

…participated in rounding up slackers, alien enemies, and German sympathizers.

(Company E, Asherville)

… very careful to watch and keep down all pro-German talk and sympathy

(Company H, Hunter)

February 16, 1918, a pro-German near Blue Rapids had become rather bold in his utterances against our country. The guard went to his home and brought him to the Commercial Club rooms. He was persuaded to kiss the flag, swear allegiance to the United States, and to pay $100 to the Red Cross. This prompt action of the guard checked pro-Germanism and aided in the collection of the Red Cross funds.

(Company A, Blue Rapids)

While such activities by the State Guard were not coordinated at the State level, neither were they discouraged. In speeches to State Guard companies in April 1918, Gov. Capper “…affirmed that no traitorous or disloyal person has a right to live in Kansas and enjoy the protection and benefit of its laws,” and that “There can be no half-way loyalty at this time. You are either for the United States or for the Kaiser. You have got to line up with Uncle Sam or leave Kansas.” The following month, Capper stated that “Among the most important activities of the state guard has been the rounding up of slackers and German sympathizers.” However, Capper also warned the Guardsmen against taking the law into their own hands.

In 1918, steps were taken at the state level to revive the National Guard and to create two new infantry regiments. It was hoped that State Guard units would volunteer for service, but “Much to the surprise and disappointment of those interested in the organization of the National Guard, the opportunity of entering the National Guard service met with little response from members of the State Guard units,” even though the new regiments were prohibited from serving overseas. By the end of the war in November 1918, only seven companies of the State Guard had mustered into the new Fourth Infantry Regiment. The organization of what was to be the Fifth Regiment was never completed.

In Europe, an Armistice was signed which ended the fighting as of Nov. 11, 1918. With the end of the war, many State Guardsmen lost their enthusiasm for continued service. Private Elza D. Liby wrote to Gov. Capper in December 1918:

“I am riting you a few lines this eavining to ask a favor of you. “As I belong to the State gards Co. C. 39 Battalain at Solomon Kans I would ask of you to help me get a discharge on the grounds of enterfearing with my work as I am a married man and have a wife and two children and work at the Farmer’s Elevator Co. at Solomon Kans it is a very hard matter for me to be present at all the drills so I thought it would be better for me and the rest of the conpany if I could get a discharge. “So I will ask this favor of you.”

Private Liby was killed in a work accident before his request was acted on. In April, his company was mustered out at the request of its members.

Although a few companies voluntarily maintained an active existence, most were soon mustered out. On Oct. 15, 1919, Gov. Capper issued an order disbanding the State Guard, effective Nov. 11, 1919.

The Kansas State Guard had done its part in transforming Kansas from a sleepy state at peace to one mobilized for war. Its contribution was summarized in a wartime speech that Gov. Arthur Capper gave to a company of State Guardsmen:

The state guard is not a “tin soldier” organization. It is not a picnic society. It is not made up for show. It means hard work for every member of it. It means a sacrifice of time. It means self-denial. But it is a duty which must appeal to every patriotic man who is able to carry a rifle ….It is a big thing that you are doing, It is a big thing whether you ever see a day’s active service in the field or not. The mere fact that you have voluntarily enrolled yourself as soldiers of the state, ready to defend with your lives the institutions of the state, and to see that the laws of the state are obeyed, is a stimulus to the patriotism and the loyalty of the whole people. The sight of you men meeting together of your own free will and accord, to engage in military drill, cannot fail to have a big effect in discouraging disloyalty, slackerism and traitorous pro-German proclivities. The enemies of freedom, the disloyal followers of kaiserism, learn from you that Kansas is in earnest in her determination to make this state 100 per cent loyal.

(Reprinted from “‘100 Percent Loyal’: The Home Front During World War I,” Plains Guardian, vol. 45, April 2000, p. 18, by Staff Sgt. Bryce Benedict, 102d Military History Detachment, Kansas Army National Guard.)

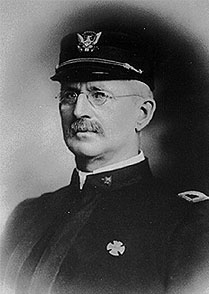

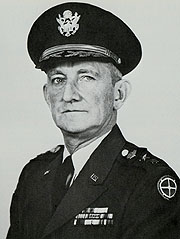

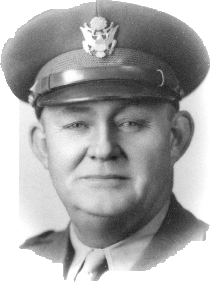

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

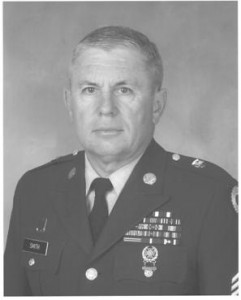

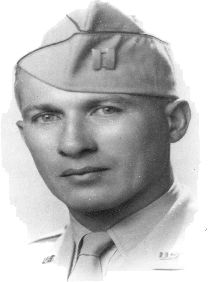

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

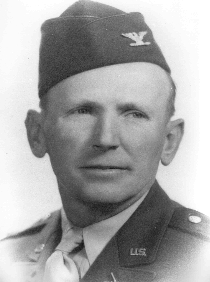

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

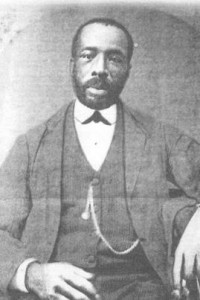

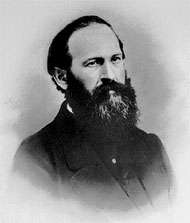

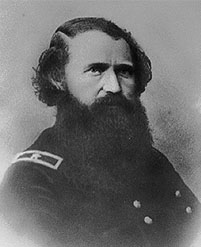

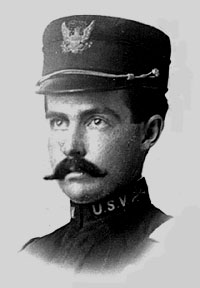

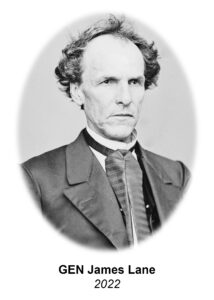

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

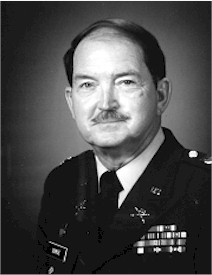

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.