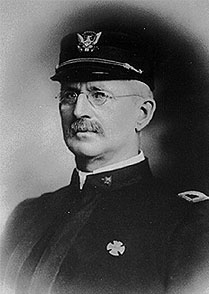

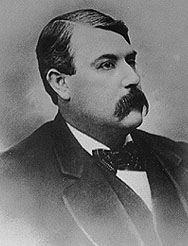

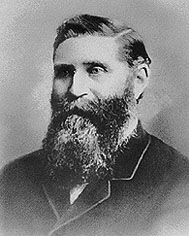

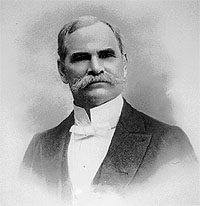

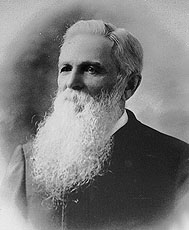

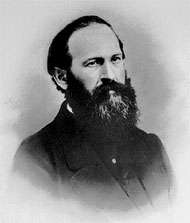

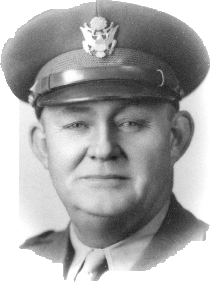

James White Frierson Hughes

James White Frierson Hughes

Kansas’ 22nd Adjutant General

April 01, 1905 – April 01, 1909

Mayor of Potwin

Mayor of Topeka

Chief of Police-Topeka

Topeka is a poorer city today because Colonel J.W.F. Hughes no longer walks its streets. He was born in Tennessee, but lived in Topeka from 1881 till his death in 1945, a period of 64 years. He was a college graduate, very intelligent, friendly, kindly, very original, vigorous in his defense of the right and of the underprivileged, extremely courageous, the essence of politeness and courtesy, a gracious host and a man of many accomplishments and talents. Colonel Hughes had a deep-seated love of city, county, state and nation. His patriotism was of the highest degree as is shown by his membership in the armed forces for most of his adult life.

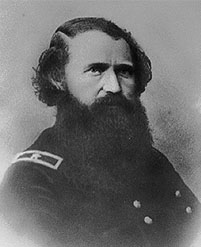

It was a consequence of his refusal, as commander of the Kansas National Guard, to obey an illegal order to eject members of the Kansas Legislature from their hall (please see related link: Colonel Hughes and the Legislative War), issued to him by Governor Lorenzo D. Lewelling in February of 1893, that Hughes became a national figure over night. He was court-martialed and dishonorably discharged, but the next Governor called him back to service and made him a Brigadier General.

The Colonel was 33 years old at the time; very alert and keen. His courage and cool head averted bloodshed. The country at large had been watching Kansas indulge in a period of political aberration. The Colonel’s actions received editorial plaudits from every corner of the United States. Two or three huge scrape books now in the library of the Kansas State Historical Society preserve the hundreds of newspaper clippings.

Colonel Hughes was born at Columbia, Tennessee, January 12, 1860. He was the son of Judge and Mrs. A.M. Hughes. He had three brothers and two sisters. He graduated from the University of Tennessee in 1881 with a bachelor of science degree in civil engineering. He belonged to an honorary fraternity and also to an engineering fraternity, both Greek letter societies. He was married on October 6, 1885, to Miss Mary Adaline Clark, the daughter of Judge and Mrs. J. T. Clark of Topeka. To them three children were born: James C. Hughes, a retired U.S. Regular Army Colonel of Artillery of Long Beach, California; Mrs. Cecial W. Meredith, of Dallas, Texas, and Mrs. Juliet Newcomb, Los Angeles, California.

Colonel Hughes was always a loyal member of the Republican Party. Soon after coming to Topeka he became a member of the Topeka Republican Flambeau Club. (John A. McCall of Topeka patented the flambeau torch of 1879). It had a membership of 200. The club took part in some of the most prominent demonstrations in the United States, among them the nomination of President Harrison at Chicago in 1888. Colonel Hughes was the captain of their drill team of 80 picked men who executed 50 military, special and secret-order movements.

Apart from activities already mentioned the Colonel’s career in local public service covered many years.

Potwin, where he lived, was incorporated as a third class city. Col. Hughes was the Mayor of Potwin in 1898-99. After Potwin was taken into the city of Topeka, he served a councilman from the 6th ward (Potwin) in 1899 and 1900. In 1901 Col. Hughes was elected Mayor of Topeka. The canvassing board elected him. The Supreme Court counted him out after he had been in office ten months. The Supreme Court ruled his opponent had won by five votes. Hughes was chief of police of Topeka in 1913 during the latter part of Mayor Cofran’s administration.

Colonel Hughes last public office was as a member of the board of education of Topeka. He was first elected in 1931 and was re-elected each four years thereafter. He was a member of the Board at the time of his death. He served as president of the Board and also as the chairman of the Building and Grounds Committee. A set of tennis courts on West 8th street in named “Hughes Courts” in his honor.

When Hughes first came to Topeka in 1881 to apply to the Santa Fe for a position in the engineering department, he presented a letter of introduction. He was told that a job he might have had was gone and asked where he had been in the thirty days since the date of the letter. The Colonel replied he had so many kinfolks it took a long time to bid them goodbye. A short time later he became chief clerk to J.M. Meade, Santa Fe resident engineer, a position he held five years. In 1886 he became roadmaster at Arkansas City. He built 155 miles of track between Arkansas City and Purcell. Soon after, he came back to his old position as chief clerk to Meade. In 1891 he resigned from the Santa Fe and became the Topeka agent of the Pomeroy Coal Company of Atchison. Two years later, he purchased the coal yard and operated it for 12 years. After his period of service as adjutant general, he worked for Arthur Capper for a year on the front desk at the Daily Capital. This was the year 1909. Then he represented the Illinois Life Insurance Company till it failed during the depression of the 1930s. From then onhe was the Topeka agent of the Northwestern National Life Insurance Company of Minneapolis. During the 1920s he served as secretary of the State Poultry Association for several years.

J.W.F. Hughes had many titles, Major General, Brigadier General, Colonel, Captain, Lieutenant, Mayor and Chief. But of them all, he preferred to be called “Colonel.” And he was greeted with respect and affection as Colonel Hughes by many thousands of Topekans for over 60 years. Born just a week before the outbreak of the Civil War, his birthplace, Columbia, was in “middle Tennessee,” a region bitterly divided in its sentiments. His father was a United States district judge who was a believer in the Northern cause. Because of this sentiment, many of his kin folks “damned” him and never spoke to his branch of the family again. During the Civil War, Judge Hughes’ property was occupied first by the troops of one side and then by the troops of the other. By the end of War, Col. Hughes was old enough to be familiar with the trappings of war. Besides that, his ancestry included an officer of the American Revolutionary Army making him eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati which was formed in 1783 as an agency for mutual help to members and their friends. Eligibility is limited by descent through males only.

Whatever may have been his incitement, young Hughes joined the National Guard of his state when he was only 14 years old. At the University of Tennessee, military training was compulsory. He received his commission as second lieutenant when he was a sophomore, having already passed through the grades as private, corporal, sergeant and second sergeant. When he graduated, June 4, 1881, he had passed through the grades of first lieutenant and captain and was assistant commandant of cadets. Among his extra curricular activities he was the drum-major of the band. William Gibbs McAdoo was the bass drummer. A photograph of that band in full dress uniform hung on the wall of his office for years. In later years when McAdoo would go through Topeka on the train, Hughes would always go down to meet him. When the Colonel would say; “Hello, Billy,” Mr. McAdoo would say that sounded fine; that he was so tired of being called “Mr. Secretary.”

On coming to Topeka, Hughes joined the Kansas National Guard in which he became Captain, Co. A, of the 3rd Regiment, August 24, 1883, and Colonel of the regiment in the following year. Following his dismissal during the Legislative War in 1893, he was successively Brigadier General and Major General of the Kansas National Guard. From 1905 to 1909 he served as Adjutant General of the State in the administration of Governor E.W. Hock.

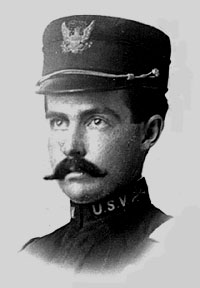

Other members of the Colonel’s family belonged to the Military establishment of the United States. A brother of J.W.F. Hughes was Archelaus Hughes, colonel of the 8th Immunes in the Spanish American War. William N. Hughes, another brother, was a U.S. Regular Army Colonel of Infantry. William N. Hughes had a son with the same regular army rank. The Col. James C. Hughes had two sons, both graduates of West Point. One son, James R. Hughes, is now a U.S. Regular Army Lieutenant Colonel on the General Staff; the other son is William R. Hughes, now a major in the U.S. Regular Army. Thomas Meredith, the son of Mrs. Alice Hughes Meredith, served in our army overseas in World War II. He was a sergeant, U.S.A.R.

The family has one interesting, non-military connection. They trace relationship to Thomas Hughes (1822-1896), English lawyer and author, who sat in Parliament from 1865 to 1874, and who wrote “Tom Brown’s School Days.”

A book could easily have been written about the beloved Colonel. He certainly supplied a wealth of material. He was a born showman; he loved to ride on horseback at the head of a parade. He just glowed when people made a fuss over him. Each year he would participate in the annual Elks Minstrel show at the City Auditorium. He was always “end man” and his costume nearly always the same boyish one. He could shake the “bones” and put on a dance just to perfection. One stunt was to fall asleep and nearly fall off his chair and then a watch, a huge alarm clock, would ring and wake him up.

He loved to play “Southern Colonel” to the ladies, bowing deeply, with a flourish, addressing all ages as “Madam,” so flattering to young women as well as to older ones. Because of the way he tipped his hat and spoke, more than one Topeka woman said she would rather speak to Colonel Hughes than to any other man in town.

The Colonel wore a white vest, broad brimmed felt hat, low cut shoes, black bow tie and collars too large for his neck, all of which set him apart from the more sober colors and cuts of his contemporaries. His coat was always unbuttoned to show the white vest, and often he walked up Kansas Avenue without his coat. Winter or summer his garb was the same. Mrs. Hughes tried every winter for the 60 years they were married to get him to wear overshoes and an overcoat; but she never succeeded.

During the years he was secretary of the State Poultry Association, he raised many chickens. He enjoyed his work. He had many runaways and small chick houses in his back yard. He tried pigeon raising, all kinds of pouters, etc., also pheasants and Japanese Silkies. He practically lived down at the city auditorium at the time of the annual poultry show. Many prizes were won by him. The large oval oak table in his living room was given him for his many years of devotion to the association and to bettering poultry strains. After many years, the table he cherished and believed solid oak was relegated to the barn, and after weathering there, it warped and turned out to be veneered. The family was amused but the Colonel was crushed.

The Colonel was a born farmer, too, but he never lived on one. He adored raising vegetables and utilized many vacant lots in the neighborhood for this purpose. Tomatoes, melons, corn, potatoes, beans and peas were some of his favorites. He loved food and was a tremendous eater in his earlier years. He made a great fuss over his food and wanted all others to enjoy theirs, too. The Colonel took eight or nine spoonfuls of sugar in his coffee. His classic story was of the waitress, who, after putting in four spoonfuls, threw down the spoon and said; “Shovel it yourself.” He did a lot of those shenanigans like using so much sugar, and later salting his drinking water, solely for effect, so some said. It created attention and interest, which he loved.

One terribly hot summer day the Colonel fried an egg on a frog of the street car track at Sixth and Kansas Avenue. The Associated Press carried the story all over the United States; the Colonel and Topeka were on the front page. His daughter, Alice, in the East at the time, felt embarrassed about it. When she returned to Topeka, she chided her father and said: “Why in the world did you do such a thing?” The Colonel replied that a reporter friend had been up to see him and had bemoaned the awful heat and lack of news and human interest stories; and that he just thought of trying to cook the egg and told the reporter to come on down to the street corner and they would “make some news.”

The Colonel was an inveterate cigarette smoker. He rolled his own from a mixture of Fruits and Flowers, with a bit of added perique, which he carried in his pocket in a metal soapbox. Carrie Nation once censored him severely for smoking cigarettes. The Colonel bowed low and commented that he had smoked them for 30 years and that God willing he would smoke them for another 30 years. The Colonel’s story of how he learned to smoke was this: He was the youngest child of six. His father was in straightened circumstances following the Civil War and couldn’t afford to purchase matches. They were too expensive. His folks smoked pipes. He was sent to the kitchen, quite a distance from where the adults were, to get coals to light the pipes. The pipes were so often cold by the time he could get clear back to his folks that he would take a puff or two to keep them going and thus save himself another trip.

In his conversation, Colonel Hughes used many unique expressions; his vocabulary was extensive. When he went to milk to cow, he would say he was going to “extract the lactic fluid from the bovine.” When he was asked how he was, he would sometimes reply “tollable like.” He used many little trick expressions of comparison, such as; “as pretty as a little red wagon”; “as independent as a hog on ice”; “as sure as Heaven made little green apples”; “as sharp as a new pin”; “no more notion what to do with it than a hog with a holiday”; “as sure as settin’ sin”; “sweet as molasses cake with sugar on it.” Certain kinds of desserts were “transparent puddin” or “atmosphere pie.” He wouldn’t eat chicken because he had raised so many. He said when he took a bite he could see his favorite poultry looking at him with reproachful eyes. Approximately 20 years ago Mrs. Hughes went on a strict diet; and made the Colonel go on it, too. It consisted of little more than citrus fruits for breakfast. The Colonel would meekly partake of the breakfast offered him and then go downtown to his favorite restaurant and eat his regular breakfast of bacon and eggs, hot cakes, toast and coffee. And he never disclosed to Mrs. Hughes that he had done so and that he wasn’t being greatly benefited by the diet.

The Colonel was an individualist if there ever was one. He lived, talked, ate and dressed absolutely in his own way. He stood out from the crowd. Everyone knew him; everyone liked him. Wherever he drove, people would call out “Hello, Colonel”; and he would reply, “Fine; how’s your family, Frank.” He was much beloved by all who knew him. He was a good man; good to his family; good to his friends. He was an indefatigable worker, he possessed tireless energy. He was up early every morning, milking the cow, feeding the livestock and tending the garden.

It was heartbreaking when his family and friends and Topeka had to part with this lovable, kindly man. Colonel Hughe’s funeral services were held in the large sanctuary of the First Presbyterian Church, his church since 1881. No mortuary chapel in Topeka would have accommodated the people and the flowers.

Taken from the Bulletin of The Shawnee County Historical Society, Number 17, December, 1952. Written by William MacFerran, Jr.

Poem “Cashiered” Written by Supporters of Hughes during his trial.

To the best of my recollection this poem was written by me I.J. Tray?, in the fall of 1893, after conclusion of the Hughes Court Martial Trial in the south wing of the state house. Mr. Gray, or Col. Hughes, had printed the poem on a sheet of paper of approximately the size of the sheet this statement is written on. I saw this poem when it was “fresh” and have a lasting recollection of Mr. Gray’s name being attached to the orginal poem. How it happened to be reprinted later, and autographed as it is, I am unable to explain.

“Guilty, as charged,” was the verdict

That came from the motley band —

From the packed “malish” court-martial

Convened at the Duke’s command;

For the socialistic Major,

And the young pop Brigadier,

And the other pop-gun warriors,

Were tools of the mighty peer.

Guilty of what? Of refusing

To do an unlawful deed;

Of failing to compass murder

To further a lawless greed;

Of saving his Royal Highness

>From a hasty trip through space,

By staying the hand of vengeance

Of an outraged populace.

“Cashiered and dismissed the service!”

And this by the wooden pegs

Who strutted around with sabres

That dangled between their legs;

Who got their clue from the Major,

Their law from an anarchist,

Their gall from as rank a party

As has ever dared exist.

And this is reform, O people!

Dash on on your senseless course,

Riding o’er law with militia,

Gaining your power by force.

Yet, spite of your old star chamber,

The “Colonel” is still ahead —

He still will be doing business

When the populist cranks are dead.

What! Down the popular dealer!

Why, blast their contracted soul,

When Duke Lewelling is busted

I still will be selling coal;

And I hope in the great hereafter,

When pops to their judgment go,

I may get the fuel contract

To warm their souls below.

September 1, 1893

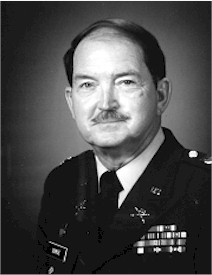

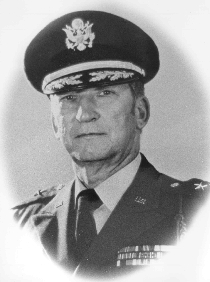

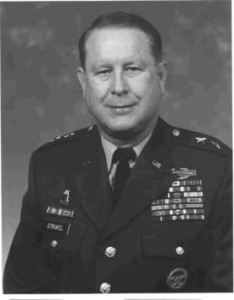

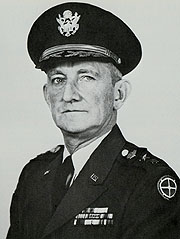

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

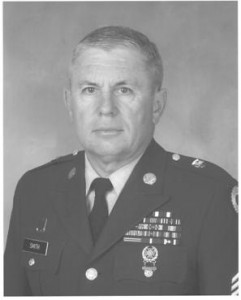

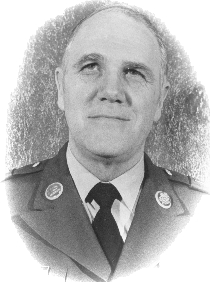

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

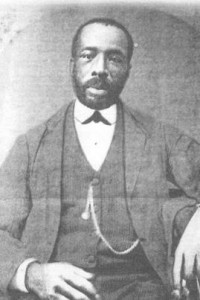

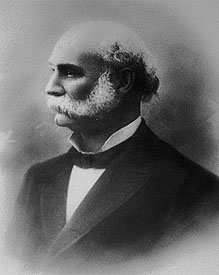

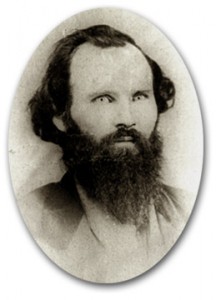

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.