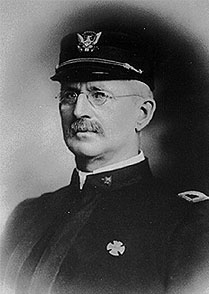

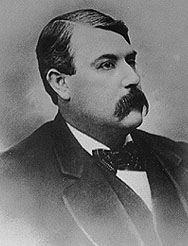

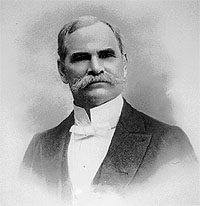

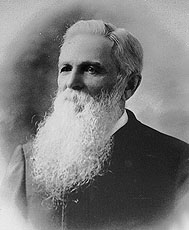

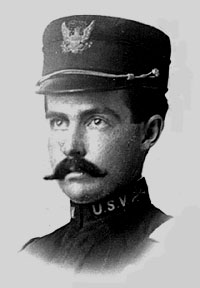

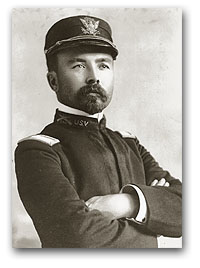

MG Frederick Funston

One hundred and six years ago a 5-foot 4-inch young man from Iola, Kan. was sliding toward the edge of a 1,000 foot gorge on the side of a mountain in Death Valley, Calif. Just a moment earlier, his horse had lost its footing on the rocky trail and although he tried as best as he could, the young man and the horse fell to the ground and slid toward certain death. Just as he was about to go over, the man was able to reach out and grab a small shrub which strained to stop his slide. He didn’t want to move too quickly, but he could see that the small shrub was stressed with his weight. The man slowly and cautiously pulled himself back up to solid ground. While he was composing himself, he turned around and looked down at his horse — 1000 feet below. Twenty-six-year-old Frederick Funston had just survived one of his lifetime’s many close brushes with death.

The future major general was born in New Carlisle, Ohio on Nov. 9, 1865, but became a Kansan at the age of two when his family settled in the southeastern Kansas town of Iola. When he was growing up, Funston enjoyed hunting, socializing with his friends and reading from his father’s 600-volume library. During high school, he helped write political speeches for his father who was a Civil War Veteran, State Representative, and later, U.S. Congressman.

After being turned down by the U.S. Military Academy at West Point when he flunked both the entrance exam and minimum height requirement, Funston taught school at a little rural schoolhouse called “Stony Lonesome” near Iola where, according to historian Thomas W. Crouch, he was forced to “trounce” the school bully, who was larger than Funston, after the student pulled a pistol on the “new little teacher.” The bully was thoroughly “corrected” but when Funston turned around after the fight, he found that all the students had climbed out the windows in fear of being hurt in the ruckus.

Funston decided to return to high school, where he graduated in 1886. Next, he attended Kansas University, where he became close friends with William Allen White, the man who would later become the famous author and publisher. Funston excelled in Spanish and mathematics and read great numbers of books on chemistry, botany, economics and other various subjects, however, he did not care a great deal about studying those same subjects in the classroom.

He never graduated from college, but he had several interesting jobs during the later 1870s including: survey work in western Kansas for the Santa Fe Railroad, ticket collector for Santa Fe Railroad and a reporter for the Kansas City Journal and the Fort Smith, Ark. Tribune. Crouch states that not long after Funston, who was a staunch Republican, began working for the Tribune, he tired of the newspaper’s pro-Democrat stances and had decided to leave.Unfortunately for his boss, Funston was put in charge of the newspaper when the management was away one time. As soon as his boss left town, Funston pulled all the pro-Democrat articles and editorials and replaced them with pro-Republican articles and scathing letters about the Democrats. Just as he had expected, the city’s Democrats were so mad that they threatened to burn down the newspaper. Funston and the newspaper’s staff grabbed weapons and readied for the attack, but his boss quickly returned after receiving an urgent telegram and fired Funston. The Kansan said, “I was tired of the rotten politics, and tired of the rotten town, and tired of the rotten sheet, and ready to go anyway, so I thought I might just as well wake the place up and let ’em know I was alive before I left.”

Funston’s time as a Santa Fe Railroad ticket collector was no less interesting. Dave Webb, in his book 399 Kansas Characters, explains: “On one trip, a huge drunken cowboy sprawled in the aisle, [laying on his back,] and began shooting holes in the passenger car’s ceiling. The 23-year-old Funston (who weighed just over 100 pounds) burst in, kicked the revolver out of the man’s hand, dragged him to the last car, and dumped him onto the rear platform.” When the train stopped Funston threw the man off, and the angry cowboy grabbed a rock and smashed a window. This made Funston so mad that he chased the man more than a mile down the track, causing the train to be delayed for a half-hour. “Another cowpoke once got on the train with no ticket. He pulled out a pistol and told Frederick, ‘I ride on this.’ Funston walked away saying quietly, ‘That’s good, that’s good,’ and soon reappeared with a rifle. He cocked the weapon, pointed it at the cowboy and said, ‘I came back to punch that ticket.’ The surprised man quickly paid his fare,” Webb writes.

It was at this point that Funston had his adventure with the 1,000 foot gorge. He had left the university, ticket punching and the rest of that life to join a group of U.S. Department of Agriculture scientists in the Dakota Badlands where he worked as a botanist collecting and studying specimens of native grasses. The scientists apparently liked his work because a year later they requested that he come with them to Death Valley, Calif., where he worked for eight months collecting different flora and fauna and helping the expedition discover 150 new species of plant life. Other than the gorge incident, Funston also survived temperatures up to 140 degrees, terrible storms, and a two-week period where the team had to eat gophers, blackbirds, badgers and chuck-wallies (a foot-long lizard) due to “someone’s inexcusable blundering,” as Funston put it, referring to a failure to send supplies.

It’s clear that Funston loved adventure because he next spent time opening up a new trail in the Yosemite Valley, living with the Panamint Indians in California, and eventually heading to Alaska where he worked again for the federal government as a botanist. Alaska provided him plenty of rugged living as he traveled 3,000 miles to the Arctic Ocean and back on dogsled and on foot, built and paddled a canoe by himself 1,500 miles down the Yukon River to the sea with hostile natives at one point shooting arrows at him, and again alone, on the banks of the Klondike River, where he endured the winters of 1893 and 1894 with temperatures that dropped to 62 degrees below zero.

After Alaska, Funston traveled to southern Mexico and selected land for a coffee plantation. He returned to Kansas to speak about his adventures and secure money for the plantation, but found that he needed additional funds. He decided to travel to New York City to get the rest. Once in New York, Funston quickly found out that not only was he not going to be able to raise additional money for his proposed coffee plantation, but that he was quickly running out of money himself. He took a job as deputy comptroller with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, where he did little other than sign his name in witnessing the execution of new stock and bonds. Three months of this type of work obviously didn’t fit the adventurer and he soon was scanning the horizon for something a little more Funston-like.

During a visit to Madison Square Garden, Funston heard a fiery speech by Civil War General Daniel E. Sicklesin in support of the Cuban insurgents in their revolution against Spain. The speech so moved Funston that he enlisted as an artillery officer in the Cuban Army even though he had never fired a cannon. He was able to get his hands on a 12-pound Hotchkiss Cannon and an instruction manual and spent several weeks training himself.

A friend of Funston, C. S. Gleed, asked why he was joining this fight and he replied, “For Free Cuba! Cuba must be cleaned up, and I am footloose and I may as well help as anybody else.” The Iola Register of March 9, 1898 gives this account of his August 1896 departure; “Starting from New York, Funston and his party were shadowed by detectives whom they dodged by neat railroad manipulation. They sailed on the Dauntless, making her first trip in a series of daring, blockade running expeditions which made her famous. Caught by a Spanish man-of-war as they neared the Cuban coast, Funston and a companion were turned loose in a row boat two miles from land, while the Dauntless escaped to the open sea.”

Twenty-three months later, the same friend who had asked Funston the question, helped take him off a harbored ship and into the hospital. He weighed 80 pounds, was very sick and was coughing up blood. During his time in Cuba, Funston had fought in 22 individual battles, had 17 horses shot out from under him, rose in rank from lieutenant to lieutenant colonel, fought on some of the same ground as Theodore Roosevelt, Leonard Wood and John J. “Black Jack” Pershing would later fight on, was shot through both lungs and an arm, had a near fatal case of fever/malaria, and finally, in a cavalry charge, had large shards of wood thrust into his hip from the roots of an upturned tree when his horse rolled over.

He knew that the wood shards would require surgery, and asked if he could take leave in the United States for medical treatment. Knowing that Funston would probably not return to Cuba, his request was granted anyway by his commander, Gen. Calixto Garcia. However, Funston was told that he would have to stealthily crawl through the brush to his transportation to avoid the enemy soldiers and the local Cuban officials who did not feel that he should be able to simply leave in the middle of the revolution. Unfortunately, he was captured by a squad of Spaniards who carried him to their headquarters in Havana for interrogation, then execution. Speaking Spanish, Funston told the men that he was an American, tired of the war, trying to get home to the United States. He then managed to do something that saved his life. He got a small piece of paper into his mouth and swallowed it. The piece of paper was his safe-passage pass, written by his commander, verifying that he was a Cuban officer and that he was to be allowed safe passage. If they would have found the passport, he would have been shot on the spot. Fortunately, this bought him time and he was eventually court-martialed by the Spaniards, who decided to release him. This was the beginning of his military career.

After healing, Funston started a second speaking tour but had his plans changed when Kansas Gov. John W. Leedy, after hearing one of Funston’s speeches, appointed him colonel of the 20th Kansas Regiment, a Kansas National Guard unit, on May 13, 1898. The 20th was one of four Kansas regiments organized after the United States declared war on Spain in 1898, but now it appeared that it would instead see action in the Philippines fighting an insurrection against the United States led by Emilio Aquinaldo. While the 20th was waiting to get into the war, Spain had signed a peace treaty with the United States giving it possession of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. However, many Filipinos followed Aquinaldo in the insurrection against the new “owners” of the Philippines. Pres. William McKinley sent U.S. forces to put down the rebellion.

The designation of “20th” was picked because the “old soldiers” of the state knew that there had been 19 regiments in the Civil War and they wanted this one to be the 20th; Funston agreed with their wishes. While the 20th was being formed in Topeka, Funston had been called to Washington and then to Florida to help plan for the war.

The 20th had been hastily formed and lacked proper military training. They were sent to the Presidio in San Francisco, Calif., where they waited. Many of the Kansans did not have uniforms (including shoes or boots), most were poorly educated and they were quickly ridiculed in the local press. They were afforded very poor living conditions and were told to set up in a low/wet area. Soldiers started getting pneumonia, measles and spinal meningitis. Only four of 12 companies had any piece of Army “blue” uniform. People from the city of San Francisco came down to gawk at the pitiful soldiers and asked them things like, “Who is your tailor?” just to laugh when the young soldiers would reply with, “We didn’t have none of them things in Kansas.” After comments like this were written in the local papers, local women, feeling sympathy, would bring the Kansans food and clothes. Their pitiful reputation would not last.

While traveling to San Francisco to join the 20th, it’s reported that Funston bought a book on military tactics and began reading it intently. His father, who was traveling with him, asked, “What do you know about military tactics, Fred?” The young colonel responded, “Not much, but I am half way through the book and by the time I reach San Francisco, I will have mastered it.”

When Funston arrived and found his men in poor condition, he immediately started drilling them in maneuvers and shooting practice. He also did his best to improve their living conditions. Due to his leadership and his presence, the soldiers’ morale skyrocketed.

After five months of intensive training in San Francisco, the 20th Kansas Regiment was sent to the Philippines, where fighting broke out in February of 1899. The 20th quickly disproved the predictions of their critics by fighting hard and winning battle after battle. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, father of Douglas MacArthur and commander of Col. Funston, sent the following wire to headquarters during the taking of the city of Caloocan: “KANSAS A MILE ADVANCE OF THE LINE. WILL STOP THEM IF I CAN.” Whether it was bravery, Funston’s leadership, the desire to prove themselves or a combination of all three, the Kansans were reported to be “taking to fighting like ducks take to water.” In 11 months, the 20th took part in 19 battles, won three Medals of Honor, had 34 killed in action and lost an additional 33 due to disease. They had become known as the “Fighting Twentieth.”

The Medals of Honor were earned when privates William Trembley and Edward White swam, under intense fire, the 400-foot-wide Rio Grande de Pampanga River and tied ropes on to the far shore enabling Kansans to follow on towed rafts. Funston was on the first raft across. The Kansans soon had a sizable number of soldiers strategically placed, attacked the enemy’s entrenched positions and drove them from the strategic location of Calumpit. Trembly, White and Funston were all awarded the Medal of Honor.

Upon their return, the 20th received great praise for the work they had performed. Pres. McKinley wrote, “The American Nation appreciates the devotion and valor of the soldiers and sailors, among its hosts of brave defenders, the Twentieth Kansas was fortunate in opportunity and heroic in action, and had won a place in the hearts of a grateful people.” Gov. William Stanley of Kansas said, “The members of the Twentieth Kansas regiment have been volunteer soldiers in an unusual and splendid sense. They enlisted for the Spanish-American War. By the terms of their enlistment their period of service expired when the Spanish-American treaty of peace was signed. Every member of the Twentieth Kansas regiment had a right to lay down arms and demand transportation home when the treaty of peace with Spain was concluded, but the thought of quitting in the face of a fight never entered the mind of a Kansas soldier… Not a man faltered, not a man stood upon his right to quit… The splendid distinction the Twentieth Kansas has won has been won while fighting after the term of enlistment had expired. It is a great regiment. All Kansas is proud of it.”

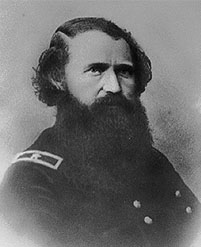

However, Funston was not done with the Philippines. He personally returned, as a brigadier general of the volunteers, and got involved in a unique operation that if it were launched today, would have been carried out by U.S. Army Special Forces. The rebel leader, Emilio Aquinaldo, had finally been located when one of his secret messages was captured. Funston carefully developed a risky plan and then sent it to his boss, Gen. Arthur MacArthur, who approved the plan but said at the launch of the operation, “Funston, this a desperate undertaking. I fear that I shall never see you again.”

Disguised as a prisoner, with 90 loyal Filipinos disguised as rebels, Funston and his team fought through 100 torturous miles of dense jungle to the area near Aquinaldo’s headquarters. Rebel forces were finally encountered near the rebel headquarters, but Funston’s team produced forged documents that fooled the rebels into thinking they were bringing the rebel leader some valuable prisoners. The plan worked so well that Aquinaldo himself sent food and water to Funston’s team, which they were very happy to take. When they reached Aquinaldo’s headquarters, a signal was given, a brief fire-fight ensued, and the rebel leader was captured. Although remnants of the war continued, this struck a major blow to the rebels. Funston returned home a national hero.

Funston was then sent to the Presidio in San Francisco, Calif. as commander of the Department of California, under the division command of Maj. Gen. Adolphus W. Greely. By sheer good or bad luck, Greely was on his way to his daughter’s wedding in Chicago when the unexpected happened. At 5:16 a.m. on April 18, 1906, Funston was awakened by a large jolt. It was a big quake, and it had destroyed a large part of the city. Funston saw that the military was going to be needed. He ordered out a majority of the troops from all military installations in the area. Funston organized and directed the soldiers to patrol against looters, guard banks and other properties, and dynamite buildings to contain the 4-square-mile fire that threatened to engulf the city.

Sometime during the next several hours, Funston sent the following telegram: “Military Secretary, Washington. We are doing all possible to aid residents of San Francisco in present terrible calamity. Many thousands homeless. I shall do everything in my power to render assistance, and trust to War Department to authorize any action I might have to take. Army causalities will be reported later. All important papers saved. We need tents and rations for twenty thousand people. (Signed) Funston.”

Just how bad was the situation that Funston faced? Within two days after the quake, every bank, hotel, and almost every large storeroom and warehouse in the city had been destroyed. Approximately 300,000 people were homeless and hungry.

Four days after the initial quake, the fire burnt itself out and Funston helped set up efficient local refugee camps, excellent ration systems and a plan for recovery. Although a small group of critics hammered Funston for overstepping his bounds of authority, he was generally heralded as a national hero and as “The man that saved San Francisco.” Some years later, Pres. Woodrow Wilson wrote the following about Funston’s handling of the great quake and fire; “His genius and manhood brought order out of confusion, confidence out of fear and much comfort in distress.”

Funston’s next excitement happened after he was sent back to Kansas at Fort Leavenworth. A “Mr. Dunawald” was upset at Funston and decided to get back at him. Dunawald had apparently been a soldier/criminal who had the misfortune of being on the receiving end of a court-martial sentence delivered by Funston. After serving his time in Alcatraz prison, he traveled to Kansas to get his revenge. The soldier went into Funston’s home and hid in the closet and when he was sure that Funston was asleep, stepped out and started shooting at him. Funston woke, grabbed a pistol under his pillow and returned fire. Neither person was hit by the brief exchange, but the soldier was later captured.

Funston’s next moment in the spotlight happened during the Mexican Border Conflict of 1914. The 49-year-old combat veteran had been sent to the area to take command of U.S. forces massing on the Texas border. This action was a response by Pres. Woodrow Wilson to the instability caused by the presidency of newly elected Mexican President Victoriano Huerta and the capture of several U.S. Marines. The city of Vera Cruz, Mexico’s chief port of entry, was ordered taken by Wilson after a German merchant ship carrying munitions for Huerta was reported heading for the port. After a brief fight inwhich 17 Americans and 200 Mexicans were killed, Funston was ordered to take 5,000 troops to the city to relieve the Navy and Marine personnel who had secured the city. He was then appointed military governor of the city.

Allen County Historical Society historian and Funston Museum Curator Michael Anderson writes, “Once in command, Funston built an organized method of administration, set up an efficient ration system and maintained civil order. Funston was an able diplomat when dealing with the local Mexican authorities, and time and again was proficient at keeping his troops out of violent confrontation. Prevented from obtaining war supplies and due to continued internal and external political pressure, Huerta was forced out of the presidency in July and fled to Jamaica. Vera Cruz was evacuated by American forces on Nov. 23, 1914. Six days earlier, Funston had been promoted to the rank of Major General [the highest rank in the U.S. Army at the time] for his successful mission in Vera Cruz. Upon returning to the United States, Funston reported on the mission as follows: ‘The best proof of the conduct of the personnel of this force during the occupation is the fact that it came among a population bitterly hostile, and, in seven months, converted that population into friends to such an extent that our departure was regretted by practically every resident in the occupied city.'”

The Major General’s final chapter of service happened in 1916, again on the border of Mexico. Revolution, the slaying of unarmed Americans in Mexico, and the raids of Francisco “Pancho” Villa north of the border had increased the tensions between the United States and Mexico. On March 9, 1916, Villa and 1,500 guerrillas attacked the New Mexico town of Columbus, killing 17 Americans. Funston recommended a pursuit of the outlaw, which was approved, however, his orders instructed him to send his subordinate, Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing (who would soon command U.S. forces in World War I), instead of going himself.

“Funston not only supervised and supported Pershing’s ‘Punitive Expedition,’ but also maintained security along the entire length of the Mexican border from the Gulf of Mexico to the California line,” Anderson writes. “Although Pershing gained the headlines, Funston pioneered what was to become a future pattern of high level military command [and oversaw the federalization of 150,000 National Guardsmen]. In addition to Gen. Pershing, Funston’s subordinates during this time included Capt. Douglas MacArthur, Lt. George Patton and Lt. Dwight Eisenhower.”

On Feb. 19, 1917, Funston was having dinner with a friends at the St. Anthony Hotel in San Antonio, Texas, close to his headquarters at Fort Sam Houston. He had finished dinner and was listening to the hotel orchestra play the Blue Danube waltzes and said, “You know there is no music as sweet as the old tunes.” “A moment later there was a sharp intake of breath, the figure relaxed, and the heart that had so often beaten the battle charge for his willing feet… the heart upon whose altars the fires of loyalty to flag and country had burned unceasingly, was still, and the dauntless spirit of the greatest and best loved military leader the United States has produced since the Civil War had taken its flight,” said his lifelong friend, Charles F. Scott.

Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston was 51 when he died. The people of Texas showed their sincere gratitude and respect by opening their most sacred shrine, the Alamo, so that he could lie in state there. He was the first person ever so honored. Ten thousand people paid their last respects to him during the three hours of public visitation.

His body was then taken to the San Francisco City Hall Rotunda, where he laid in state for two days. He was buried at the Presido in full dress uniform on a hill overlooking the city he had saved.

Had Funston lived, it is of little doubt that he would have continued to achieve great things. He never embraced the sedentary lifestyle and would have continued pursuing the “strenuous life” that his friend Theodore Roosevelt so often spoke about. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker had every intention of naming Funston commander of U.S. forces in World War I, instead of Pershing, had he not died. A less certain, but possible scenario is that he would have been pushed to be the 1920 Republican Presidential candidate. Instead, Leonard Wood ran for this position, but lost to Senator Warren G. Harding.

Funston’s old friend, William Allen White, remembered him by writing, “Only a breath of wind, the flutter of a heart, kept out of Pershing’s place in the World War, one of the most colorful figures in the American Army, from the day of Washington on down. We had a man as dashing as Sheridan, as unique and picturesque as the slow-moving, taciturn Grant, as charming as Jackson, as witty as old Billy Sherman, [and] as brave as Paul Jones.”

By 1st. Lt. Dave Young, Kansas Air National Guard

Special thanks to Funston Museum Curator Michael Anderson of the Allen County Historical Society for his generous assistance in helping produce this article.

MEDAL OF HONOR CITATION

COL, 20th Kansas Volunteer Inf

Action: At Rio Grande de la Pampanga, Luzon, Philippine Islands

Date: April 27, 1899

Inducted: Iola, Kansas.

Born: Springfield, Ohio

Issued: February 14, 1900

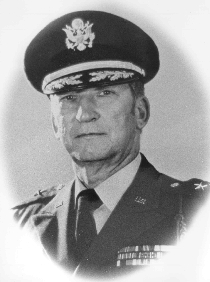

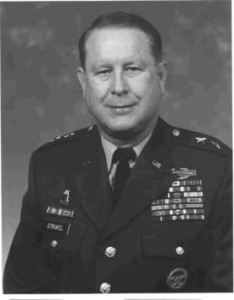

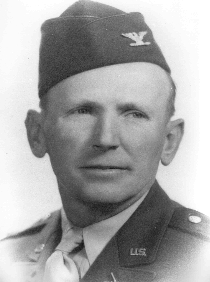

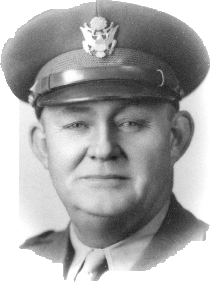

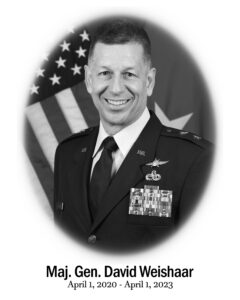

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

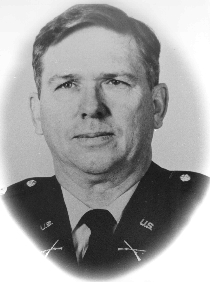

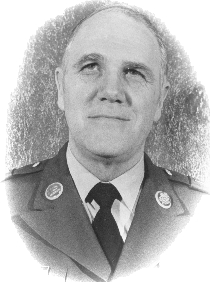

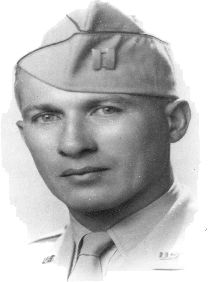

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

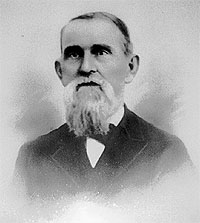

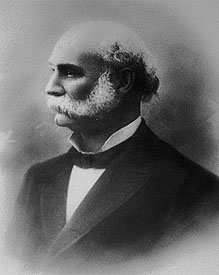

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.