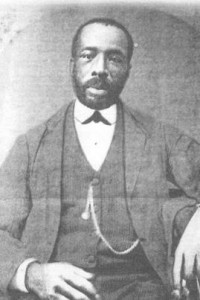

In the first weeks of the war with Spain there was an effort in Topeka to raise a company of black soldiers, but this was discontinued when it became evident that only whites would be allowed to enlist as volunteers. Councilman Roundtree of Topeka said, “We do not think that we have been treated fairly. If we have any country on earth it is this and I think we should be given an opportunity to fight for it. There are hundreds of colored people anxious to go and the only thing we ask is the opportunity. I do not know why we have been ignored.”

When President McKinley made a second call for volunteers, black Kansas citizens asked Gov. John W. Leedy to raise a regiment of black soldiers, to be officered by blacks. This was a radical proposition. Black soldiers in the United States Army were in segregated units, except that these “colored” regiments were officered by whites. Gov. Leedy was facing reelection in the fall of 1898, and saw the raising of an all black regiment as a way to bolster his chances. His announcement on June 22, 1898 that he would do this was met with an enthusiastic response from black citizens and editors of black newspapers. Elsewhere in the United States two other Volunteer regiments of blacks had all-black officers and four others had white officers except for line lieutenants.

While [black] newspaper editors proclaimed their patriotism, and were in favor of the liberation of black Cubans from the Spaniards, there was regret that more was not being done to protect blacks at home: “The Negroes of this country, while they are ready to fight the battles of Uncle Sam, are nevertheless, seriously under the impression that there are Spaniards nearer home than Spain or Cuba.”

The 23rd was formed in July 1898 at Camp Leedy in Topeka. It was not at full strength, having only eight companies; it was commanded by Lt. Col. James Beck, a black officer. While at Camp Leedy the men of the 23rd received uniforms, rifles and other equipment. As a result when they left camp they were far better equipped than the three regiments of white Volunteers that had preceded them.

In Cuba the Spanish forces at Santiago had surrendered on July 4 and peace negotiations began. A peace protocol was reached on Aug. 12 in which it was agreed that control of Cuba would pass to American hands. In the meantime American troops [in Cuba] were falling ill and dying from tropical diseases. Army officers there, including Theodore Roosevelt and Leonard Wood, circulated a “round robin” letter to Maj. Gen. Shafter, in which it was alleged that “the Army must be moved at once, or it will perish.” The Army decided to replace the troops with regiments which were thought to be resistant to tropical diseases as these regiments had been recruited from the South, or were composed of blacks.

In August orders came for the 23rd to be sent to Cuba. On Aug. 22 with much ceremony the regiment was sent off by Gov. Leedy and the citizens of Topeka; from there it traveled by rail to New York. According to the Kansas Adjutant General, the regiment: sailed from New York on Aug. 25, on the steamer Vigilancia for Santiago, Cuba, arriving there Aug. 31, 1898. The regiment proceeded immediately by rail to San Luis, reaching that point on Sept. 1. Hostilities having ceased, the duties which devolved upon the regiment, although arduous, were of a peaceful character. Excellent discipline was maintained and all duties were cheerfully and faithfully performed.

The extreme southern portion of Cuba was occupied by American troops, while the rest of the island was being shared uneasily by the Spanish and the Cuban guerrillas. In Santiago sanitary conditions were appalling. A naval captain remarked that even before the war, “You could smell [Santiago] 10 miles at sea.” The city had had no drainage system other than open street gutters. Now, after years of guerrilla warfare and a siege by American troops, Santiago had become much worse. It was plagued by small pox, typhoid and yellow fever. Dead animals littered the streets, and in many homes the dead were left to rot. Food was in short supply. The surrounding countryside was not much better.

Brig. Gen. Leonard Wood was in command of the zone occupied by American troops. He took immediate vigorous steps to improve conditions in Santiago. Local citizens were recruited, sometimes by force, to collect the dead. There were so many corpses “that they had to be collected in lots of ninety or a hundred, placed between railway irons, soaked in petroleum and burned outside the city.” The streets were cleaned of debris, and food was distributed to the hungry. Wood’s public works programs provided income to thousands of unemployed Cubans, including members of the Cuban Army. This substantially encouraged the Cuban Army to disband, thereby removing a potential threat to the American troops. To combat bandits Wood organized a Rural Guard made up of Cubans; his idea was not to risk American lives but to “Let the Cubans kill their own rats.”

By the time the new regiments arrived the city had been thoroughly cleaned, the death rate checked, and food was being widely distributed. Wood’s public works program, employing mostly Cuban labor, continued. In Santiago “Even the streets were sprinkled with disinfectants. Inside of four months Santiago was probably the cleanest city in tropical America. It smelled to heaven of disinfectants, but it was clean.”

The 23rd was one of three black regiments sent to do garrison duty in Cuba. The other two were the 8th Illinois and the 9th Volunteers. The officers of the 8th Illinois were black, while the 9th, from Louisiana, had white officers except for its line lieutenants. The first duty of these regiments was to take charge of five thousand Spanish prisoners of war awaiting their repatriation to Spain; and then they “turned their attention to the task of assisting in the rehabilitation of San Luis Province. They constructed roads and bridges, repaired streets and plazas, and engaged in various projects designed to improve sanitary conditions.”

A week after arriving in San Luis Capt. William B. Roberts of the 23rd wrote that:

We are camped on the outskirts of the town, just across the branch from the 8th Illinois regiment, and have met several of the officers and think a great deal of them. All are getting along nicely together. Our men visit back and forth and have a good time.

We have but little [sickness] in camp, most of what we have is bad colds and malaria. We have 24 men in the hospital but none seriously sick. It is impossible to keep from taking cold until a person gets acclimated. It is very hot in this climate and the nights are cool enough to sleep under blankets and it rains every day. Big dews fall at night. So you see the weather conditions are much different to anything we have been used to, but I [am] feeling fine, except a slight cold, and am trying to keep well.

There is no yellow fever here, but a good many cases in Santiago, there being two hospitals for fever patients.

This country is five hundred years behind ours. Little dirty streets, with houses worse than our barns, made of bark from coconut trees which are the most common trees here….

This is a great country of possibilities, but poverty reigns supreme. The fields are grown over…and are as wild as they ever were in the world. The people are pitiful sights, nearly naked and half starved little bony boys, girls, women and men….

The barracks where the 8th Illinois is quartered is an old Spanish prison and there are all kinds of cruelty and butchery–beheading blocks all covered with human hair and dried blood, and pieces of rope still hanging from the old round rafters, where many a poor unfortunate Cuban had been hung. Old bloody blankets were carried out of the hospital department of that old crib of a barracks, where Cubans had been butchered and burned by the [Spanish] soldiers ….

It is reported that there are 1500 Spanish soldiers in the hills [and they have been given a deadline to] lay down their arms, and if they do not comply, we will have to go out and bring them in; and these 2,000 Negro troops here are the ones who can and will be pleased of the opportunity to do it. We hate the Spanish more and more every day as we see the result of this ten years’ war and

the confusion, for they have made a barren tract out of a once fertile field.

A month later Roberts wrote that:

You need not think that because there is no active fighting to be done here that we have nothing to do, for we are constantly doing guard duty, and it is a battle to ward off these dreaded fevers and malaria, which has made such a havoc in the ranks of United States troops, and we have to take medicine as a preventative. I never believed in medicine at home, you know, but here I am great friend to quinine, and barrels of it is used by us soldiers on the island and we must take it or be sick.

The three black regiments were ordered to move their camps farther outside of San Luis after soldiers from the 9th Volunteers got into a firefight with local Cubans on November 14. Some drunken soldiers from the 9th had stolen a pig, and hostilities escalated when the Cubans tried to recover it. Several Cubans, and one man from the 9th were killed.

The Kansas Adjutant General concluded the official history of the 23rd as follows:

The regiment camped in the vicinity of San Luis until Feb. 28, 1899, when it proceeded by rail to Santiago, where it embarked on the steamer Minnewaska, on March 1, 1899, and sailed for Newport News, Va., arriving there March 5,

1899.

On March 6 the regiment proceeded by rail to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., reaching that point on the 10th of same month. The regiment was mustered out on April 10, 1899.

The 23rd Kansas was an organization that soon became thoroughly drilled and maintained at all times excellent discipline. The officers were all men of intelligence, and the enlisted men obedient and prompt in the performance of all duties required of them, and the regiment received the commendation of the officers under whose command it served. The state of Kansas may be well proud of the record of the 23rd Kansas.

The 23rd had 14 men die while in the service. Ten of the deaths were in Cuba from disease; the other four died stateside – two of disease, one was killed in a railroad accident and one was stabbed to death in Missouri as the regiment made its way home.

(Reprinted from Benedict, Bryce D. “23rd Kansas Volunteers Mobilized To Cuba,” Plains Guardian, August 1998, pp. 16-17. Note: despite the excellent performance of Black soldiers in Kansas units during the Civil War and in Cuba, it was not until the 1950s that Blacks finally entered the Kansas National Guard on a permanent basis.)

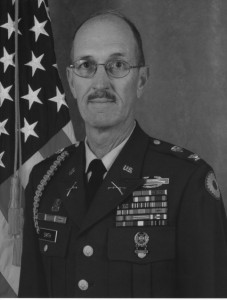

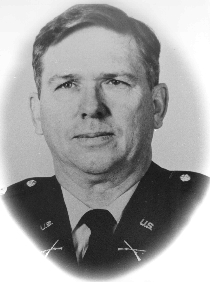

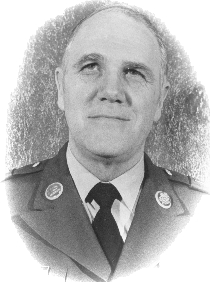

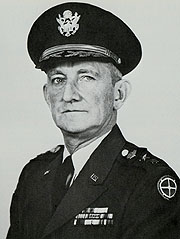

Maj Gen David Weishaar

Maj Gen David Weishaar

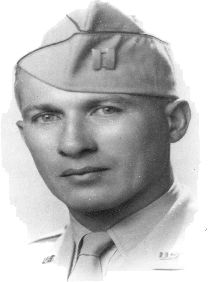

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail.

First Sergeant Darrel W. Haeffele was born on September 25, 1940, in Falls City, Nebraska. He graduated from Atchison High School in 1958. He attended Concordia College in Seward, NE for two years before starting a career in retail. CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law.

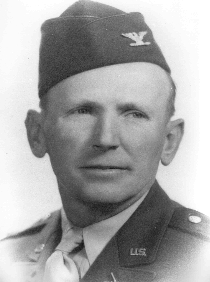

CW5 Roland E. “Ron” Kassebaum was born on February 21, 1946 in Deshler, Nebraska. He graduated from Hebron High School, Hebron, Nebraska in 1964. He attended Fairbury Junior College, Fairbury, Nebraska and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, and received a Bachelor of Science Degree from the University of the State of New York in 1991. He later attended Liberty University, Lynchberg, Virginia, for courses in accounting and Allen County Community College, Iola, Kansas, for a course in Business Law. Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968.

Chief Warrant Officer Four Ronald E. Mullinax was born on August 25, 1946, in Norton, Kansas to Earl and Mary Posson. He was adopted by John and Ada Mullinax. He grew up in Lenora, Kansas, graduating from Lenora Rural High School in 1965. After completing a Denver Automotive Institute training program, Ron worked at Look Body Shop in Norton until 1968. CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist.

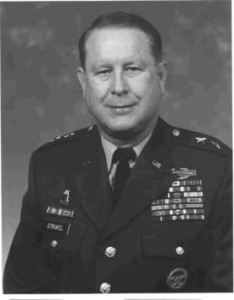

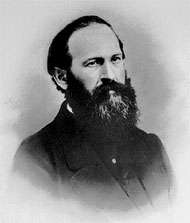

CCMSgt Valerie D. Benton was born on Dec. 10, 1959 in Racine, Wisconsin, where she spent her childhood. She graduated from Washington Park High School in 1978. Soon after graduation she enlisted in the U. S. Air Force and headed to Basic Training at Lackland AFB, Texas in December of 1978. After completion of Basic training, she attended Technical Training at Lowry AFB, Colorado, and graduated as a Food Service Specialist. Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas.

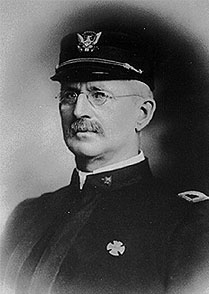

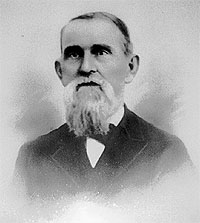

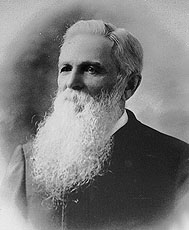

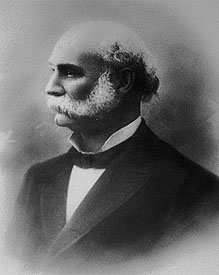

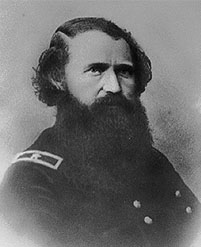

Brigadier General Jonathan P. Small served as The Adjutant General of Kansas from November 1, 2003 to January 4, 2004, culminating a 35-year military career as a distinguished attorney, community leader, citizen-soldier, and military leader. He served as Assistant Adjutant General-Army from 1999 to 2003, and as Commander of the Land Component for the Joint Force Headquarters-Kansas. General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas.

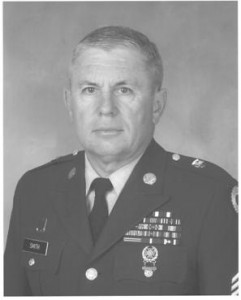

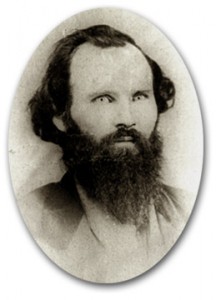

General James H. Lane was a militia leader during the Bleeding Kansas period, the commander of the Kansas “Jayhawker” Brigade during the Civil War, and was one of the first United States Senators from Kansas. Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years.

Sergeant Major Joseph T. “Jody” Muller was selected for the Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame for his exceptional service as a citizen soldier in the Kansas National Guard for over 41 years. Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Master Sergeant Greg Gilroy was born on July 25, 1947 at Ottawa, Kansas. He was a lifelong resident of Ottawa, graduating from Ottawa High School in 1965. He then attended Emporia State University during the 1965-66 school year.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Brigadier General Deborah Rose entered military service with a direct commission into the United States Air Force Nurse Corps in March 1983, assigned to the 184th Tactical Fighter Group. She transferred to the 190th Clinic in December 1985. In October 1990, she deployed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she served in an Air Transportable Hospital during Desert Shield. In February 1991, she was activated and deployed to Offutt AFB, Nebraska, assigned to the hospital.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.

Sergeant Major Lynn E. Holt built his distinguished Kansas Army National Guard career developing strength, retaining Soldiers and insuring Soldiers received proper training. He served from the Detachment through State level. He is known for his ability to recognize Soldier needs at all levels. The same care he felt for Soldiers carried over into his community activities. SGM Holt’s passion for people and their needs exemplifies his true character. He devoted his entire adult life to the betterment of our nation, our state and the Kansas National Guard.